6

Visitors

Commander Carey had had very few visitors since he had settled in the house on windy Guillyford Point, renaming it Buena Vista rather as a joke, but also in memory of his fighting days off the Spanish coast. It had been very pleasant indeed to see young Johnny Corcoran; the lad had come on splendidly in the past three years or so, and altogether he had enjoyed the short visit very much. It was a pity that Johnny had had to hurry on north again to report to his Papa.

Commander Carey felt nevertheless much brightened by the episode, and a couple of days later was in his pretty front garden, where he did most of the work himself, tying up a rambling rose, and whistling cheerfully, unaware either that he was doing so or that it was a rather unaccustomed sound, in the precincts of Buena Vista.

“Good morning!” called a cheerful young voice.

The Commander looked up with a start. He did not know any very young ladies, and he most certainly did not know this pretty, fresh, pink-cheeked face. He came uncertainly over to the gate. “Good morning.”

Although the man was in rough working clothes, with a homespun shirt and his sleeves rolled up. Pansy had seen immediately from the eye-patch that he must be the Commander himself. So she replied, beaming, and unaffectedly holding out her hand: “It is Commander Carey, is it not? I’m Pansy Ogilvie: my sister and I are staying in Elm-Tree Cottage, on the outskirts of the village.”

Numbly Commander Carey, who was not accustomed to a lady’s offering a handshake in this way any more than he was to lady callers, shook hands over his little blue-painted gate. “How do you do, Miss Ogilvie?”

“I’m very well, thank you, and this isn’t a social call: I’ve come about your boat,” said Pansy briskly.

“My boat?” he said numbly, glancing down to where she was moored out in the bay.

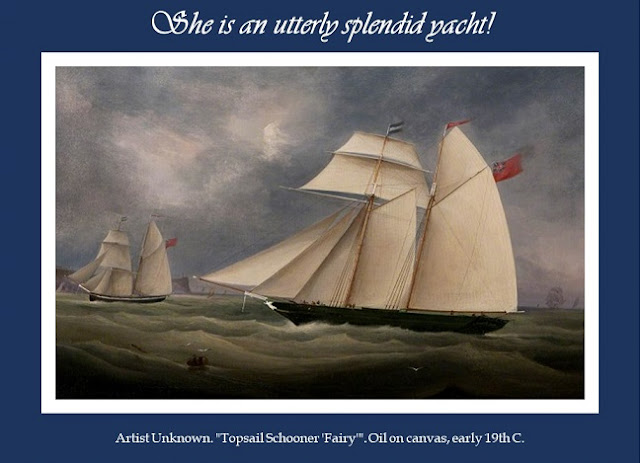

“Not Finisterre, sir!” said Pansy with a grin. “Though she is an utterly splendid yacht!”

“Aye, she is not a bad craft,” agreed her proud owner.

“I like the name; do you in fact sail her out of sight of land?” asked Pansy.

“Er—frequently, ma’am,” said the sailor weakly.

Pansy sighed deeply. “I thought you must. And of course you have seen Cape Finisterre yourself?”

“Many times.”

“Yes. I do so wish I were a man: it is so unfair! And you were at Trafalgar, were you not?”

“Indeed. Though that was not all the great fun you seem to imagine it, Miss Ogilvie,” he said wryly, touching his eye-patch.

“Of course I don’t imagine it to have been fun; nor do I imagine battles to be nothing but gallantry and—and derring-do!” said Pansy crossly. “I am not such a gaby! I am aware that, on the contrary, they result in great destruction, pain and suffering. l am frankly convinced that only the male half of humanity would have been so stupid as to invent them. And very evidently it is only the male half of humanity that is so stupid as to continue the tradition of fighting them, instead of finding a rational solution to political problems! –No, but to lead a life of strenuous action at sea, that is what I would wish for! If I had my dearest wish,” she said, narrowing her eyes, “it would be to go on a voyage of discovery like Captain Cook, to Otahiti and Australia!”

Commander Carey was now frankly grinning. “I, too, Miss Ogilvie! Only it does not always fall to our lot in life, to have our dearest wish, does it?”

“No. And I was born a girl, so I shall never have mine,” said Pansy, pulling a horrible face. “But I’m rambling, sir: l have come not about Finisterre but about the small boat which they tell me in the village you have for sale.”

“The sailing dinghy? Why—yes. But...”

“l am quite a competent sailor: I was taught by old Mr Bill Dawson from Sandy Bay. He tells me he knows you,” said Pansy, fixing the Commander with a hard eye. Indeed, Commander Carey who, when he was not being a man of action, was a voracious reader, felt himself forcibly to be in the position of Mr Coleridge’s unfortunate wedding guest. Miss Ogilvie lacked but the long beard: she had the glittering eye.

“Yes, I know Dawson,” he admitted. “He was with me at Trafalgar.

“I know.” Pansy looked at him hopefully.

“Er, it is not a light boat, Miss Ogilvie,” he said weakly.

“Pooh, I can handle Mr Dawson’s dinghy alone!”

“Aye, but does he let you?” retorted the Commander on a dry note.

“Um, well, no, he or his grandson always come with me, but I don’t need their aid. And I’m not stupid, sir: l wouldn’t take her beyond the bay!”

The Commander looked doubtful; Pansy urged: “Try me!”

Commander Carey’s long mouth twitched into the beginnings of a smile. “Aye, well, it’s great sailing weather.”

“Yes, indeed! Come along, shall we go directly?”

“Er...”

“Are you going to be so prejudiced as to refuse me, just because I am a female?” demanded Pansy grimly.

Suddenly the memory of another determined young woman who was convinced she was as capable as any man came back to Leith Carey. He was a trifle shaken: he had not thought of Naomi Blake this many a long year. It was true she had never expressed a desire to sail a boat, and certainly not single-handed, but—

“No, Miss Ogilvie, I think I can rise above that sort of prejudice, at my age. I shall just have to leave a message so that my mother does not worry about me, and then we may be off.”

“Oh, good!” she cried. “They say you have a big telescope,” she added on a hopeful note.

At this the Commander frankly grinned. At first, what with her lack of shyness and self-possession, he had taken her for a grown-up young lady, however eccentric. But now he realized that she could be little more than a schoolgirl. “Aye, but if you dally playing with it, we shall miss the tide. You may look through it when we return.”

“Thank you so much!” she beamed.

“Wait here; I won’t be a minute.” He ran up the front path, smiling.

A narrow track led down from the cliff top to the tiny cove where Buena Vista’s boathouse stood. The Commander preceded Miss Ogilvie down it, for he was a little afraid she might stumble, but she proved as nimble as he.

She launched the dinghy and set sail competently. The Commander sat back, watching her.

After a few moments he murmured: “There is a nasty eddy in the lee of the Point: It can be very dangerous when the wind is from the other direction.”

“A little further up the Point, yes, I know: one risks being blown onto the rocks. Mr Dawson told me, and I have seen it for myself.”

“I think, Miss Ogilvie, you must be the young lady who helped Dawson and one of his grandsons to rescue some fool who had sailed into the eddy, not long since. Back at Easter, was it not?”

“Yes. It was very exciting,” said Pansy, squinting up at the sail. “Jibe HO!”

Commander Carey ducked, the boom swung over, and they embarked on a fresh tack.

“Of course it was very scary, at the same time,” she admitted. “I was terrified the man would drown before our very eyes.”

“Mm. A battle provokes very much the same mixture of emotions.”

“Yes.” Pansy glanced at his eye-patch but said nothing.

After a moment Commander Carey murmured: “May I ask how old you are, Miss Ogilvie?”

“I am older than Matt Dawson, at all events!” she said crossly.

“I was not thinking of that...”

Pansy looked at him uncertainly. “Seventeen. And a half. Well, almost.”

The Commander’s lips twitched. “I see. Well, in the light of your expressed views on the foolishness of battle and those who engage in it, I suppose you are old enough to hear that yes, the loss of my eye did hurt extremely.”

Pansy bit her lip, and nodded.

“Not so much at the time, for I fainted, but certainly afterwards. After the damned surgeon had removed the organ, you understand.”

“Yes,” she gulped.

“Never had so much rum, before or since,” he said reminiscently. “It was a pity I was not in a fit state to enjoy it.”

“Oh,” gulped Pansy. “I see. Did they— Was that what they used as medicine, sir?”

“Aye. Well, there ain’t much else on a man-of-war with half her rigging shot away and her main deck in splinters. But yes: the theory is, if you pour enough rum into a man he’ll be so drunk he either won’t feel or won’t notice the pain.”

After a moment she asked on a fearful note: “Did it work?”

“To a certain degree,” he replied tranquilly.

Pansy’s big brown eyes had filled with tears. She concentrated fiercely on her sail in silence for a while.

“Perhaps I should not have spoken,” he murmured.

“No,” said Pansy, swallowing. “Of course I was wondering about it. And it was... salutary. And I apologise for being so rude about—about fighting men.”

“Oh, but I entirely agree with you, Miss Ogilvie,” he sad with a strange little smile. “There is nothing so idiotic as the idiocy of risking one’s life and health for the sake of a few yards of disputed territory.”

“Are you glad to be retired, then?” she demanded.

“No. –Such is the perversity of man,” he noted.

“Yes!” she said with a little startled laugh, looking at him for the first time with not only respect but also the realization that he was an unique individual and not a type.

Commander Carey caught the look quite clearly. He could not have said why, but he smiled right into the brown eyes and said teasingly: “Shall I be a-takin’ of the sheets, Cap’n Pansy?”

“No!” said Pansy with a gasp and a laugh. “Oh, dear, you sounded so exactly like Mr Dawson! Except that he always calls me ‘Liddle Missy.’ No, truly I can handle her, sir.”

“I can see that. Well, I shall be more convinced of it once you have reached the farther side of the bay, come about and, let us say, sailed us out opposite the end of the Point, come about once more and got us into the jetty. And tied up.”

“You really intend to test me!” said Pansy pleasedly. “Well, I have done all that an hundred times with Mr Dawson.”

“Good.” Commander Carey lay back at his ease with his arm along the side of the boat, lazily watching her.

Leith Carey was, of course, a man of seven and forty. He did not for a moment think of pretty little Pansy in a romantic way: for one thing, he was more than old enough to be her father. But his imagination was greatly tickled by her manner and her forthright and original mode of speech, and he was not unimpressed by the fact that her claim to be “quite a competent sailor” was evidently true. And then, if he was not young, he was not yet immune to the pretty pink cheeks and the curls that peeped from beneath a rather squashed straw bonnet, or to the big brown eyes or the tears that had sparkled in them when he had spoken of his wound. –Why he had spoken of his wound, which was not something he was at all accustomed to do, he did not pause to wonder. Nor did he pause to reflect, voracious reader though he was, that it was not unknown for an unlikely romance to flower between an old warrior and a young lady, a case in point being that which the gentleman in question—whose occupation, incidentally, was also gone—had summed up as: “She loved me for the dangers I had passed, and I loved her that she did pity them.”

The little voyage was accomplished in fine style and Pansy brought the boat neatly into the jetty, having managed to call Commander Carey a lubber only once, when he had vetoed the notion of sailing on westwards along the coast for a way, it being a pity to waste such a glorious day.

“Well?” she said eagerly.

The suggestion that they set sail in the English Channel for the sunset had confirmed in Commander Carey an earlier suspicion that, however genuine she might presently be in declaring she would not attempt to sail out of the bay, when Cap’n Pansy found herself at the tiller in great sailing weather any such promise would fly out of her head. So he said reluctantly: “Much though I would like to sell her to you, I really feel that you are too inexperienced to take her out alone.”

Pansy’s face fell. “But if I promised always take someone with me, sir?”

“What if you could not find anyone to go when you wished to?”

She scowled. “You have seen that I can handle her by myself!”

“Yes. I’ve also seen some nasty weather blow up out of nowhere in the Channel. Indeed, just off the Point.”

“You would not be saying this if I were a boy!” she cried.

The Commander scratched his chin. “I think I would, you know. If you were a boy with as little experience as you have. Um... Might I suggest that we take her out together sometimes?”

Pansy was very upset indeed: she had really thought she had had him convinced. “No!” she cried angrily. “I am not a little girl, to be given treats! And I wish to be independent, and my own man!”

Commander Carey’s wide mouth twitched and he had to swallow a cough. “Yes; I do understand. Is there no-one who might contract to come out with you on a regular basis?”

“No-o... Well, the thing is, Commander.” she confided, looking up at him with big innocent eyes: “I haven’t very much money. My sister and I are not sure how long we may be fixed at Elm-Tree Cottage, and we have to husband our resources very carefully. I did think of hiring Matt Dawson to be our garden boy and crew for me at need, for the men do not want him on his father’s boat and there is very little for him to do at Sandy Bay. But on examining our finances I concluded that I could not afford both the boat and Matt.”

“I see. Er—perhaps if I merely hire you the boat?”

Pansy flushed. “Actually, I was going to suggest that anyway.”

“Well, yes— Oh, I see. You mean you cannot afford to buy her?”

“No,” she owned glumly.

“Cap’n Pansy, you have dragged me all around Guillyford Day on false pretences, when I might have been tending to my roses!” he said with a laugh.

Pansy peeped at him. “Aye: only there be nothin’ like sailin’, when all’s said and done!”

“Now it is you who sound like Dawson!”

“Yes!” Her smile faded and she said: “I did not intend anything underhand, sir.”

“No, of course you did not. Well, talking of roses, I need a garden boy myself, but the local boys are such dashed rascals, I have hesitated to hire them. But if he would come over to these foreign parts, Matt Dawson would be the very thing. Do you think he would come?”

“I think he would, sir. He is very tired of the way his grandfather puts him down all the time. Not that Mr Dawson does not love him: it is just his way. But really, he does not give Matt credit for his competence, and it is beginning to chafe him. And then, his mother is forever ordering him about, and he doesn’t like that, either.”

“Aye. Well, I should be forever ordering him about here,” he said on a dry note. “How would that suit Master Matt, I wonder?”

“He would love it!” she cried with sparkling eyes. “You are a real Royal Naval commander!”

“Er—aye. Well, shall we try it? On the understanding that unless there is a positive emergency in the garden, such as all the runner beans being flattened by a storm, you may have first call on his services when it is good sailing weather?”

Pansy went very pink. “Are you sure you are not doing this just for me, sir?”

Of course that what precisely why he was doing it. Commander Carey smiled and assured her the garden was become far too much for him: he had sown seed madly and now could not keep up with the results. He arranged briskly the terms on which Miss Ogilvie would hire the Poppet, and suggested that for the nonce they keep her in her boatshed. Pansy consenting to this, they set off again for Buena Vista’s tiny beach.

Commander Carey had not supposed his charming new acquaintance would have forgotten about the telescope, and so it proved: at the top of the cliff path she said in a squeak: “If it is not inconvenient, may I look through your telescope, sir?”

“But of course!” he said with a laugh. “I have it in my study, right at the top of the house; we call it the crow’s-nest: I hope you are accustomed to scaling the rigging, Cap’n Pansy?”

Pansy assured him she was very fit. She accompanied him happily into the house, looking about her with great interest at the evidences of the Commander’s travels in foreign climes.

Commander Carey did not take her in to meet his mother: he thought that Miss Ogilvie was young enough and excited enough about the telescope not to notice the omission. And so it proved. She applied her eye to the eye-piece enthusiastically and soon had the trick of adjusting it.

The telescope was mounted in the large gable which the Commander had had built out of an attic room when he had purchased the house. He had had to carry out considerable repair work before the house was liveable and had taken the opportunity to make the alterations which would also help make shore life bearable for him. The gable had windows on all three sides and gave a splendid view out over the Channel and up the coast. The room itself was a good size, lined with bookshelves, and was filled besides with things such as charts and large seashells and brass-bound chests and—

“Is that a sextant?” asked Pansy excitedly when the environs of the Point and vast spaces of the English Channel had been inspected.

“Certainly,” he said, very surprized that she should have recognized it.

“Oh, sir, would you teach me navigation?” she cried eagerly.

“What, on Poppet?” he replied with a twinkle in his eye, thinking she was pretty much of a poppet herself, especially when her eyes sparkled and her cheeks became all flushed up over some unlikely subject.

“No! No, we could do the theory upon dry land and—and put it into practice, if you should not dislike it, upon Finisterre.”

The Commander rubbed his chin. “Finisterre is not precisely a smooth ride for a young lady, you know.”

“Nothing makes me sick! I have never even been slightly queasy with Mr Dawson, and we have once or twice run into very choppy seas!”

“Mm. Navigation requires considerable mathematical knowledge.”

Pansy smiled at him. “My papa was a mathematician, sir, and I have passed all the examinations he ever set for his pupils at Oxford. If I was not a girl, I would have an Oxford degree myself.”

“I see! Er... Well, it ain’t that I’d doubt an Oxford fellow’s word, y’know—”

Pansy giggled, and shook her head. “No! Go on, try me.”

The Commander duly tried her. Pansy solved the problem he set her in a considerably shorter space of time than it took him to check her answer.

“Er—yes. Perfectly correct. Er—but what would your sister say to the scheme?”

She looked blank.

Commander Carey rubbed his chin. “There are only myself and my mother in the house, you know.”

“Oh: you mean would Delphie think it proper? Well, if your mother lives with you, can there be any objection?”

The Commander swallowed. “In theory, no.”

“I could start any time it suited, sir,” she said hopefully.

“Are you quite sure you wish to embark on this? I’m said to be a hard taskmaster.”

“I don’t think you could possibly be harder than Papa. He was used to forget entirely such minor matters as meals or bedtime, when he was teaching a subject which interested him.”

“I’m not that bad, but I come down hard upon lazy midshipmen who don’t do any devoirs I may set ’em,” he said with a grin.

“It will be a pleasure to have something to exercise my mind on,” replied Pansy with a sigh. “It’s not that I’ve been bored, precisely, since Papa died, because for—um—various reasons, I’ve been very busy. But I have had no true intellectual work, and have begun to feel latterly as if my mind was under-exercised. Set me as many devoirs as you please, sir.”

“Very well, then. Shall we say, tomorrow at ten? Oh—I am also very down upon tardiness.”

Pansy held out her hand. “So am I. It’s a bargain, then!”

A trifle limply the Commander shook the little strong hand. His own utterly engulfed it: nevertheless Cap’n Pansy had quite a grip: all that rowing! he thought, feeling a bubble of laughter rise in his throat.

He was about to show her out when there was a hasty tap on the door and the housemaid came in, panting.

“What is it, Mary?” he murmured.

“Sir: Mistress asks me to ask you—will you step downstairs—please, sir!” she gasped

“Pray get your breath, Mary: is it as urgent as all that?”

The girl panted, and gave him an agonized look.

“Very well, I shall be down directly,” he said calmly.

“Hullo, Mary; so this is where you work?” said Pansy, smiling at her.

“Good-day, Miss!” she gasped, still panting.

“Mary’s father runs the tavern in the village, did you know, sir?” said Pansy to the Commander.

“Yes, indeed, and many a barrel of excellent ale has Mr Potter sent up to me,” he replied with a twinkle.

“It was for a barrel my sister and I called there, actually—though not of ale!” said Pansy with a laugh.

“No: it were for an empty!” gasped Mary.

“Yes: my sister wished to plant a root of mint, and she had heard that if you plant it in a barrel it will prevent it from running all over the garden.”

“Aye,” agreed Mary, apparently having regained her breath. “Master, he’s got one here, Miss: out in back, it be.”

“Yes; it is an excellent notion,” the Commander agreed. “So you met Mary there, did you, Miss Ogilvie?”

“Yes: she was helping out, were you not, Mary?”

“Aye: I often does on my day off.”

“Of course,” agreed the Commander, going over to the door. “This way, Miss Ogilvie. –And was your father able to supply a barrel, Mary?”

“That he were, sir,” she agreed, following them downstairs. “It were a bit cracked, like, but naught to worry if you don’t go a-puttin’ of liquors in it. –And Ma said I was to say if I saw you, Miss, that at this time o’ year a bit o’ parsley and some chives, they will do right well, and never do the mint a mite of harm. And Ma puts pansies in hers, too, only that be just to pretty it up a bit, like.”

“Aye: a pansy will pretty up many a cracked old vessel,” agreed the Commander smoothly.

Pansy choked.

Mary emitted a delighted cackle. “That be a good one, Master!” she gasped. “Beggin’ your pardon, I’m sure, Miss!”

“No, I agree, it was a good one. An inspired one, even. –I collect you’re a Cambridge man, Commander?” Pansy added smoothly.

Commander Carey’s shoulders shook but he answered calmly enough: “Not I. Sent to sea at fifteen.”

“Not really?” she said weakly.

“Yes. Most of my life has been spent at sea.”

“Master has medals an’ all. And he lost ’is eye in the great sea-battle where Lord Nelson, he was killed,” said Mary solemnly to Pansy.

“Yes, I know, Mary. It was a great and tragic day for England.”

“Aye, it were that, Miss. Pa says as how Vicar, he didn’t know whether to be ringin’ a peal for the great victory or tollin’ the bell for Lord Nelson’s death. And when he done read it out in the church, the tears was a-runnin’ down his face.”

Pansy swallowed. “Yes,” she said in a stifled voice.

“Well, it is all over now, and the Admiral is laid to rest, God bless him, and we have finished off Boney and the Frogs for good and all!” said Commander Carey on a bracing note. “Run along, now, Mary; I will see Mistress directly.”

Mary bobbed, bade Pansy good-day, and retired.

Pansy’s trim little figure had scarcely reached the blue-painted gate when there was a screech of rage from the direction of the sitting-room and the crash of some friable object’s meeting the floor. Wincing, the Commander hastily closed the front door.

“Mamma, pray do not upset yourself like this,” he said firmly, going in to her.

Old Mrs Carey was frail, but she was not bedridden, the which in the opinion of Commander Carey’s servants, all of whom were devoted to him, was a great pity. It meant she could come downstairs whenever she wished and poke her nose into everything and take umbrage without rhyme nor reason at anything and everything—or at nothing at all.

“Who was that?” she said crossly. “Leith, why must you continually invite visitors into the house without bringing them in to me?”

“Mamma, you are exaggerating. I brought Lieutenant Corcoran into you and he spent some time with you.”

“Who?” she said crossly.

“Lieutenant Corcoran, Mamma. The young man who was here a few days since.”

“I do not know any Lieutenant This, That or the Other! And what was that girl doing in my house?”

Reflecting that it was a great pity that the sitting-room was so conveniently placed for a view of the front gate, the Commander replied: “That was a very young lady, in fact almost a schoolgirl, from the village, who wishes to hire my boat.”

“What? What?” she said querulously, putting a hand behind her ear.

Many physicians had assured Commander Carey that his mamma was not in the least deaf. He responded soothingly: “No-one that you need worry about, Mamma.”

“What? What?”

The Commander swallowed a sigh. “Nothing, Mamma.”

“Some little hussy, no better than she should be,” she muttered to herself. “With an eye on your fortune, I have no doubt!”

“Mamma, I have no fortune!” said the Commander, rather loudly.

“What? What?”

“I have no FORTUNE!” he shouted.

“Pray do not shout at your mamma, Leith. And please do not utter such absurdities!” She gave a titter of laughter. “Why, I have counted these many years on Cousin Griffin’s leaving his fortune to you and Barnabas, and so he will, mark my words!”

“Cousin Griffin died twenty years back, and he left his fortune to his second wife.”

“What? What?”

“I said Cousin Griffin is DEAD!” he cried. “I have no FORTUNE, Mamma!” –Oh, dear, this was ridiculous; and in any case dear little Pansy was not after his imaginary fortune!

“They are all dead!” wailed Mrs Carey, bursting into tears. “Cousin Philip Carey, and your Papa’s dear brother Lionel, and Cousin Bethel Anderson, and Aunt and Uncle Anderson, and my dearest Cousin Alphonsine!”

“Who?” said the Commander numbly in spite of himself.

“And now you tell me poor Cousin Griffin has passed on!” she wailed.

“Mamma, Cousin Griffin died TWENTY YEARS AGO!”

“What? What?”

“And Uncle Lionel died before I was even born, and old Cousin Bethel was eighty if she was a day,” he muttered.

“And why does Barnabas never come to see me?” she wailed. “They have all forgotten me!”

“Barnabas is in India, Mamma,” said the Commander clearly and slowly. Not in the hopes of being listened to, however.

“A boy like him? What have they sent him out there for?”

The Commander sighed. Barnabas Carey was fifty-two and had been in India for the last thirty years. Well, it explained why he rarely came to see his mamma—yes.

“Most regrettable, Mamma,” he said politely.

“Regrettable! I should say it is regrettable! He will never his promotion that way!” She went on for some time about General Carey’s supposedly blighted career but just when her son was certain she had side-tracked herself broke off to demand: “And who was that flibbertigibbet in the dowdy pelisse?”

The Commander made the mistake of returning: “What flibbertigibbet was that, Mamma?”

Immediately she hurled another china ornament to the floor. “I will not have these hussies pursuing my son in my own house!”

Resignedly Commander Carey rang the bell for Mary. Personally he didn’t care how many pieces of china his mother broke, they were all hers, and all hideous, and she never came up the steep stairs to his “crow’s-nest” where all his most valued treasures lived. But it was a little hard on the servants.

He sat with her for some time and she gradually calmed down and got off the subject of flibbertigibbets and his imaginary fortune and began to talk quite rationally about going into the village tomorrow to pay a call on the Vicar’s wife. Commander Carey agreed to this plan, though he knew that on the morrow she would have forgotten all about it. Or remembered that she hated the Vicar for his failing to read out the anniversary of Mr Peter Carey’s death in church. Or, most likely, both. Perhaps needless to say no-one had ever apprised the Vicar of this significant date and as the Careys were not a local family there was no way he might have been supposed to have been aware of it.

Old Mrs Carey was, very obviously, somewhat senile. Some might have adjudged this a tragedy; but she had never been a particularly bright woman, and had had no intellectual interests whatsoever. Nor had she been a particularly pleasant or generous-hearted woman, and the senility had merely served to exaggerate these traits in her. It would have been impossible for any rational being to have been fond of her and Commander Carey had long since recognized he was not; but he was prepared to do his duty by her. It could not have been said that he was happy in his home, but he was more or less resigned to the situation. And when he was in his crow’s-nest or out on Finisterre he was as perfectly happy as it was possible for a man who had lost his occupation of the last thirty-two years to be.

His mother no longer dined downstairs: after his solitary dinner Commander Carey went up to his crow’s-nest and got out all his old navigational textbooks. He did not give his mamma another thought that evening. And he had completely forgotten that he had meant to tie up his roses that day. And, though the sudden thought of Naomi Blake had at one moment given him quite a jolt, he did not think of his old love, either. By the time he retired that night, the crow’s-nest was exceedingly ship-shape and Bristol fashion, and two chairs were drawn up to the big desk in the window, ready for Pansy’s lesson.

He went to bed and dreamed he was at sea, with fair weather, a following wind and a good ship beneath his feet.

“You called on this Commander Carey?” gasped Delphie on Pansy’s return.

“Yes!” she beamed. “And it’s true that he has a patch over one eye and was wounded at Trafalgar: he told me all about it! And he is going to let me hire his boat and teach me navigation! I have had the most glorious day of my entire existence!” cried Pansy ecstatically, hurling her bonnet in the air. “Huzza! Huzza for Commander Carey!”

“You cannot have been at his house all this while!” she gasped.

“No! Imbecile! We took Poppet out for a trial run round the bay. He let me do it all,” beamed Pansy. “And he needs a garden boy, so he’s going to hire Matt Dawson, and Matt will be able to crew for me!”

“Er—good,” said Delphie numbly. “Pansy—”

“And he has a real naval telescope and he let me look through it! And he’s so intelligent, Delphie!” she said eagerly. “Even though he went to sea at fifteen—imagine! His crow’s-nest is lined with books, he must be almost entirely self-taught. Oh, sorry: that is his study, where he has the telescope. And he has such a sense of humour!”

“That’s nice,” said Delphie weakly. “Pansy—”

“At first you think he is such a sad man,” said Pansy on a dreamy note, “and then he gives a funny little smile and you see he has a great sense of fun. Though clearly he is a most serious person.”

“Yes. Pansy, I thought he was a—a single gentleman?”

“What? Oh—yes, he said there was only him and his mother. And I think the village stories about her must be true: she was throwing things.”

“Dearest,” said Delphie with a troubled look, “you did not visit in his house, did you?”

“Yes, of course! The telescope is in his study.”

“Pansy, that was not at all the thing! How could you? Oh, dear, it was very heedless!”

“Don’t bawl, Delphie,” said Pansy with a sigh. “Can’t you be glad that I’m happy?”

Delphie gulped. “I— Of course I do not want to spoil your fun, dearest. But can’t you see... Well, how old is Commander Carey?”

“Um... Not as old as Papa. But he is an older man. More than old enough to be my papa. And most respectable.”

“Well—well, how old?” she said on a weak note.

“Oh, I would say at least fifty,” replied Pansy hazily. “His hair is quite grey.”

“Oh. Well, perhaps… .And the mamma was at least in the house?”

“In the sitting-room.”

“That does not sound too... But I think I should meet him, if he is to teach you navigation.”

“Splendid: you will see for yourself he is harmless!” said Pansy with a laugh. “You may come with me tomorrow: we have an appointment for ten o’clock. And if you dawdle I shan’t wait: I don’t want to give him the impression that I’m not serious about it.”

Delphie was quite sure she wouldn’t give him that impression: no. Then an awful thought struck her. “Pansy, did you—did you talk the poor man into these navigation lessons?”

“No. Well, I asked and he was very glad to do it. I think he’s bored with a land-lubber’s life. Well, after being at sea ever since he was fifteen—!”

“My goodness, yes. –I think it would be best if I met him.”

Pansy nodded.

After a moment Delphie said: “Um—what does he look like, dearest? Apart from the grey hair.”

“And the eye-patch.”

“Er—of course.”

“Um... Well, I don’t know! You’ll see him tomorrow. Um... Like I said, he’s old. Um—well, his one eye is blue: it’s all lines, like this,” said Pansy with a smile, tracing horizontal wrinkles with her forefinger by her own round brown eye. “You can see he’s used to looking great distances, at sea... He’s not fat.”

“No?”

“No. And quite tall. He favours one arm. I didn’t ask him about it but l noticed it when we were docking. Mr Dawson said he caught a ball in the shoulder in his last sea-battle, so I suppose that was it. And he’s lost a couple of fingers.”

“Ugh!” said Delphie with a little startled shudder.

“Losing the eye was worse.” Rapidly Pansy reported what the Commander had said.

Delphie’s hands went to her face. “No!” she gasped. “Dreadful!”

“Yes: he and I are agreed that war is dreadful. Also an idiocy.”

“Ye-es... But dearest, he has been a Naval officer for his entire career, surely you—he— Are you sure you did not put words in his mouth?”

Pansy grinned. “I’m very sure I could not! He has a mind of his own, you will see! No: why should not a thinking man decide for himself that war is an idiotic and wasteful way of settling disputes, even if his family has set him to a Naval career?”

“Well, if you put it like that, there is no reason he should not, of course.”

“No, quite. It’s so good to meet someone who can think for himself and is not wholly bound by—by hidebound prejudice!”

Delphie did not pretend not to take the reference. “Pansy, that is most unfair: you said yourself that Miss Blake has a fine mind!

Pansy sniffed a little. “Mm. But she has a habit of tempering the expression of any original thought she may have with the judgements of society, have you not noticed?”

“Er—well, yes. But that is natural, given her profession.”

“No,” said Pansy, narrowing her eyes. “I grant you that her profession entails her tempering her behaviour to suit the requirements of society: but not her thoughts!”

After a moment the Professor’s elder daughter agreed: “You are right. Not her thoughts. Indeed, there is something almost immoral in doing so.”

“Yes. The Commander isn’t like that,” said Pansy confidently.

On reflection, Delphie did not know if she was glad or sorry to hear it.

Miss Blake received a visitor on the very day that Pansy was having her first navigation lesson. He was not wholly unexpected: after hearing from the parent or guardian of B.A. and B.C., she had more or less been in expectation of some communication from L.A.’s papa.

Colonel Amory offered his excuses for not having made an appointment, and produced Lizzie’s letter. He did not know if perhaps Miss Blake might be aware of this matter—?

“Yes: it has recently been brought to my attention. But thank you so much for coming to me, Colonel Amory,” she said. “I can assure you that the matter has already been dealt with.”

“Dealt with?” he said on a startled note.

“Indeed,” she confirmed. “The Miss Ogilvies are no longer with the school.”

“But surely—! My dear Miss Blake, I am aware that such a matter could not be overlooked, but—but they are such very young creatures, was there not some way—er...”

“I have a responsibility to the parents of my pupils. Colonel: I did not feel that I could keep them on, after they had practised such a deception. Even though it was with no real evil in mind.”

“Evil! I should think not! A pair of girls like that! Why, they are scarce older than your older pupils, surely?”

“Miss Ogilvie—that is, Miss Philadelphia, who is the elder,” said Miss Blake with a frown, “is full five and twenty years of age, Colonel. More than old enough to be aware of what she was doing and of its consequences should she be found out.”

He swallowed. “Miss Delphie is twenty-five?”

“Precisely.”

“I see.” He hesitated. “My little Lizzie has become so very fond of her over these past few months...” he said in a low voice.

“Yes, I know,” replied Miss Blake with a sigh. “It would have been that, that would have persuaded me to keep her on, if anything could. But you must see that it was impossible.”

Colonel Amory also sighed. “Yes. I must admit my mother feels quite strongly about the business.”

“That is understandable.”

“I—I wonder if you could perhaps explain some of the circumstances, Miss Blake? They seemed such very pleasant young women; what can have driven them to such a step?”

“Well, there were certain mitigating circumstances. And they come from an unconventional background: although it is hard to credit it, I really believe they thought themselves to have no other resource.” She explained in some detail.

Colonel Amory listened intently. “Thank you,” he said at last. “I see it all, now. I agree there was little option open to you, Miss Blake: of course it would not have done to permit them to stay on...” He swallowed. “But two such innocent young creatures, abroad in the world: what will become of them?”

In the presence of a parent, Miss Blake felt a trifle guilty that, far from casting the Ogilvies adrift in the world, she had taken very good care that no harm should come to them. So she replied on a colourless note: “I have contacted their relatives. And at the moment I believe they are situated comfortably enough.” –She had not herself seen Elm-Tree Cottage but Mrs Warrenby had assured her it was perfectly clean and comfortable.

“That seems satisfactory,” said Colonel Amory weakly. “But I wonder... I am rather worried about Lizzie. Would it be possible to furnish me with their direction, Miss Blake?”

Respectable parent though he was, Miss Blake did not feel she could furnish a widower in his mid-forties with the direction of the Miss Ogilvies. She replied on a firm note: “I think Lizzie will get over the whole thing very much faster if she has no further contact with Delphie, Colonel. It seem a little harsh, but I can assure you that in such cases a clean break answers best in the long run. –Now,” she said, rising, “I am sure you will like to see her.”

Colonel Amory rose politely. He did not insist, for he was as aware as she of the ineligibility of his contacting two young, single ladies who were at the moment without a protector. But his brain began of itself to revolve ways and means.

He did not, at this moment, examine his motives in wishing to contact the young women. And perhaps he was not ready admit to himself that it was not entirely for his little Lizzie’s sake. But certainly his heart had leapt in his breast at the news that Miss Delphie was full five and twenty years of age.

Lizzie came shyly into Miss Blake’s study and gave a polite little bob. But after the headmistress had kindly left them alone she burst into tears and ran into his arms, sobbing: “Papa! Delphie has gone away!”

“I know, my love,” he said steadily, hugging her very tight. “But don’t worry: we’ll find her again.”

“Promise!” begged Lizzie, gulping.

“I promise, my angel,” said Colonel Amory, kissing her limp brown hair. “I promise.”

Miss Blake’s letters had by now of course been dispatched, but she was not in expectation of receiving any response as yet. She was thus somewhat surprized when, two days after Colonel Amory’s visit, on a windy, blustery day with a lot of racing cloud, the sort of day, in fact, on which the normal desire is to do nothing more energetic than curl up by the fireside with a good book—and possibly a plate of muffins—Pointer came into her sitting-room in the late afternoon with a very odd look on her face and informed her there was a gentleman come to call.

“Thank you, Pointer. Will you show him— What is it?”

“Miss Blake, he’s got a wild animal!” she gasped.

Letitia Worrington who, being off-duty, was ensconced by the fire, at this gasped and dropped her book on the rug.

Miss Blake could only be thankful she had not as yet rung for the buttered muffins which they had been contemplating. Calmly she murmured: “A wild animal?”

Pointer nodded hard. “A-settin’ on his shoulder, it be, on a chain, Miss Blake, only that didn’t stop it from a-hurlin’ of ’is hat across the hall!”

Miss Worrington gave a little squeak.

The Ogilvies’ description of their papa’s eccentric friend came back forcibly to Miss Blake. She rose, a little smile hovering on her firm mouth, and said lightly: “I suppose the gentleman does not have a talking bird on his spare shoulder, Pointer?”

Miss Worrington gasped.

“No, Miss,” said poor Pointer numbly.

“Never mind, Pointer, I think I know who the gentleman is. You had best ask him to step into my study. –And ask him if he or the monkey would care for refreshment,” she added on a dry note.

“Yes, Miss. It ain’t like no monkey as I ever heard tell on, Miss Blake.”

“I think it must be a South American marmoset. Hurry along, Pointer: the gentleman has come a long way and is probably rather chilled.”

Pointer bobbed and hurried out.

“The poor little monkey is undoubtedly even more chilled, on a day like this,” noted Miss Blake, inspecting her hair in the mirror over the mantel.

“Naomi, who is he?” quavered Miss Worrington.

“Dr— Er, I forget his name, Letitia. But I think it must be an acquaintance of the Ogilvies’. The monkey is most likely one that their papa brought him from South America. But I own I am disappointed he did not bring one of the parrots,” said Miss Blake, going out with a gleam in her eye.

“Parrots! Wild monkeys!” lamented Miss Worrington, left alone in the comfortable little sitting-room. “Dear, oh dear! –And what if it bites?”

What, indeed? But Letitia Worrington did not have the intestinal fortitude to hurry after her headmistress and warn her of this eventuality. Not when Naomi was receiving a gentleman. However odd.

The gentleman standing before the fire in the study and unaffectedly warming his coat-tails was a tall, burly, untidy personality with rumpled pepper-and-salt curls. Miss Blake experienced quite a little shock as he looked at her and smiled: she did not know why, but although the Ogilvie sisters had assured her that Dr Whoever was not old, she had somehow had the impression— But this man could be no more than her own age.

“How do you do, sir?” she said steadily, coming forward. “I am Miss Blake, the headmistress here.”

“Yes: young Pansy described you pretty exactly,” he said cheerfully.

“I did not catch your name, I’m afraid, sir,” replied Naomi Blake, very firmly indeed.

“Oh: Fairbrother, ma’am. Wynn Fairbrother. How do you do?”

He was holding out his hand, so although it was not the done thing for a lady to shake a gentleman’s hand, at least in the southern counties of England, Miss Blake shook it firmly. Dr Fairbrother did not have the sort of wide, squashy hand that often went with that sort of burly build: he had a large, strong, hard hand. With a few odd stains on it: perhaps he indulged in chemistry as well as zoology? The untidy brown coat had a few odd stains on it too, but his waistcoat, though somewhat old-fashioned, was respectable enough, and his linen was sparkling clean.

Wynn Fairbrother had been intrigued by Pansy’s description of Miss Blake: he had thought a headmistress must be merely prunes and prisms, but Pansy had made it very clear that Miss Blake, though behaving with the propriety expected of one in her position, was not that. He looked at her with the frank interest with which he was accustomed to examine any new creature which had caught his attention. Pansy had not described the headmistress’s physical appearance in detail, but she had said she was tall and quite handsome: he perceived that she was very tall for a lady and, though not pretty, indeed quite handsome. He liked the wide grey eyes and their steady glance. And her shaking hands like a man was a relief: usually they expected you to kiss the damned things like a Bond Street beau!

“This is Percival Cummings the Second,” he added, gently touching the little monkey which was clutching his neck.

“He seems a little shy,” said Miss Blake.

“Yes: he’s not much used to travel. But I couldn’t leave him behind, he’s been raised by hand from an infant and would pine if left alone.”

“I see,” she said, smiling at the burly man and his tiny pet. “Might I ask where the name comes from, Dr Fairbrother?”

He grinned. “I was wondering if you were politely going to ignore that, the meanwhile bursting with frustrated curiosity! You’re only the... let’s see... the fifth person to have asked me that outright, ma’am. And only the second one over the age of forty,” he added on a dry note.

Miss Blake’s smooth cheeks flushed a little at having had her age so accurately—not to say brazenly—calculated by this complete stranger, but she replied composedly enough: “So shall you tell me?”

“Oh, certainly. Percival Cummings the First is a Fellow at my college—old college, I suppose I should say: they don’t approve of the natural sciences, you see. Long since chucked me out. Well, largely because I refused to pay lip-service to the notion of a creating deity. I think creation’s marvellous enough in itself.” He gave her a mocking look. Miss Blake did not react. Grinning, the zoologist said: “Old Percy Cummings looks dashed like a marmoset. Frill of white hair and so forth. Has a partiality for nuts and fruits, too!”

“I see,” said Miss Blake, trying not to laugh.

“The other persons who asked me straight out, since you don’t ask, ma’am,” he said on a dry note: “were young Pansy Ogilvie, which I imagine you might have guessed, my eight-year-old nephew, the baker’s little daughter, who’d be around ten, and the Master of Balliol.”

Miss Blake choked.

“There are those who maintain the scholarly mind must retain the curiosity and forthrightness of the child,” he said sedately.

The ladylike, proper Miss Blake went into a gale of laughter, and Wynn Fairbrother grinned all over his cheerful face.

“Oh, dear!” she said, wiping her eyes. “But this will not do: pray be seated, sir. I collect you have come to speak to me about the Miss Ogilvies.”

“Yes, of course. Blotted their copybooks, I gather,” he said cheerfully, sitting down by the fire.

Miss Blake took the place opposite. “Yes.”

“Um—well, Pansy wrote me the whole. Can’t imagine why they didn’t appeal to me earlier. Not that I have tuppence to bless myself with! Only— Hold on, perhaps if you read her letter.” He produced Pansy’s letter.

Miss Blake took it a trifle uncertainly. But still, if the man wished her to—

“Fair?” he said as she finished it.

She jumped, and handed it back. “Yes, that is a very fair summation of the position. Pansy has a very clear mind.”

“Yes. Unconventional, though, especially to a lady like yourself.”

Miss Blake replied coolly: “I think we can agree that Pansy has made it very clear that my life is necessarily ruled by convention. Unlike her, I do not find that a matter for lamentation. On the other hand,”—she fixed him with a cold grey eye—“I am not seventeen years of age.”

“Aye. She’s pretty green,” he said mildly. “They don’t understand the meaning of the word ‘compromise’ at that age, of course. Let alone of the word ‘moderation’! Well, the thing is, Miss Blake, that I’ve been to see old Humphrey Ogilvie. Thought it was the only thing to do. He ain’t precisely mad as a hatter, but acting as if he is gives him the opportunity to abdicate all those responsibilities he’d rather not have.”

“I see.”

“I was sure you would,” he said with a twinkle in his clever brown eyes. “Of course the girls didn’t get anywhere with him—not even Pansy, though she’s a strong little character. The only tactic to use when a fellow’s gone that way is outright bullying. So I bullied him. –Here,” he said, delving into his pocket again.

Miss Blake took the slip of paper and gasped.

“Did Pansy tell you he’s a very warm man? Inherited a fortune from a brother. Never spent a groat of it.”

“Yes, but this is a bank draft for five thousand guineas!”

“Yes. I was going to make it pounds, but I thought, Why not? Well, it will keep them in modest comfort for life, poor girls,” he said kindly.

Miss Blake attempted to hand it back to him.

“Er—couldn’t you look after it for them, ma’am?”

“I am not their guardian, Dr Fairbrother. And since it was you who—who managed to—er—”

“Make the old goat cough up. Mind you, that’s not quite fair. Goats are rather pleasant creatures, when you get to know ’em,” he said with a glint in his eye.

Miss Blake ignored, with some difficulty, both the glint and the remark. “Since it was you who obtained this princely sum for them, sir, I feel it should be you who presents it to them.”

Dr Fairbrother took it with a sigh, and put it in his pocket.

“And since we are on the subject, may I ask who, if anybody, is in fact their legal guardian?” she added.

He rubbed his nose. It was a very ordinary nose, rather knobby, if anything; not in any sense a handsome or classical or even a Roman nose, and Miss Blake, who had hitherto believed herself an admirer of only the most chiselled of features, could not imagine why she found it rather a pleasant nose. In fact the whole face was pleasant. Though there was nothing handsome about it.

“I think Delphie is Pansy’s guardian,” he said. “Well, that was how old Quentin intended to leave things. I don’t know if he ever got around to it—nothing to leave, the annuity died with him. Only that was his intention. And Delphie’s too old for a guardian.”

“In years: possibly,” she said grimly.

He laughed. “Little Pansy’s always been the stronger character! Very like Quentin! –Have you heard the episode of his pet monkey and the neighbour’s prized China hen, ma’am?”

“No. –Thank you, Pointer,” she said as Pointer came in with a laden tray.

“Yes, Miss Blake,” said Pointer, eyeing the monkey. “The gentleman said as how something warm would be desirable, Miss Blake, and seeing as how you said—”

“Yes, very good, Pointer,” said Miss Blake somewhat weakly, perceiving that Pointer and Cook between them had sacrificed the burgundy that she produced only for very august male parents indeed. Or when she had the Bishop to dine.

Pointer’s eyes remained fixed on the monkey. “And the currants and that be for the little animal, Miss: the gentleman said—”

“Yes: perfect, thank you, Pointer, he will be very pleased with those!” said Dr Fairbrother heartily.

“Yes, sir. Cook wondered if the little beast might care for some of this peel, as well, sir. Only we was not sure if it would drink from a saucer like Horatio Nelson or a cup like a Christian.”

The reference to the great Admiral did not cause Dr Fairbrother to so much as blink. He replied, smiling: “Oh, Percival Cummings the Second will sit up and drink his draught like a Christian!”

“Very good, sir,” said Pointer, removing a saucer from under a small glass.

“Thank you, Pointer,” said Miss Blake hurriedly. “That is excellent.”

“It smells wonderful!” said Dr Fairbrother, rubbing his hands, as Pointer withdrew, still with an eye on Percival Cummings the Second.

Weakly Miss Blake offered him mulled burgundy and hot buttered muffins. Oh, well, it was a nasty day. And burgundy could be replaced.

“Horatio Nelson is a cat,” she said abruptly as the zoologist, having seen that his little pet was embarking on the currants, sank his teeth into a muffin.

Dr Fairbrother nodded round the muffin.

“Oh—of course: you must know him,” said Miss Blake limply.

He swallowed, nodding. “Aye. A fine beast. Good ratter. Is he here, or does Pansy have him with her?”

“She has him. I think Pointer and Cook miss him. And the girls also, of course.”

“Just as well: Percy here can’t stand him. Oh, that reminds me of what I was going to say!” He took a second muffin and embarked on the story of the professor’s pet monkey and the neighbour’s prized China hen. The proper Miss Blake laughed until she had to mop her streaming eyes. And—regrettably—not least at the part Dr Ogilvie had played in the drama.

“What was its name?” she asked eagerly, stowing her handkerchief away.

“Mm? –Ooh, look, Percy: this is a fine fruit-cake!” He made a series of chirruping noises, offering the little creature a tiny piece of cake which was mostly fruit. Percy chittered at him, and took the fragment of cake.

“His hands are so tiny,” said Miss Blake in a weak voice.

“Irresistible, are they not?” he said with a smile. “Percy’s my barometer for telling the worth of a human being. If they neither smile at the feathery ears nor go all weak at the knees at sight of the hands, Percy and me don’t want to know ’em, do we, sweetheart? Mm?” He chirruped at him again: the monkey chirruped back.

“Weak at the knees?” said Naomi Blake limply.

Dr Fairbrother gave her a mocking look.

“Oh, dear,” she said with a foolish smile.

“Oh, Percy’s little hands reduce even strong men’s knees to water, ma’am.”

“Those of the Master of Balliol, no doubt!” returned Miss Blake with vigour.

“Very possibly; but I didn’t need to inspect ’em, ma’am, for he was already smiling at the ruff-like effect of the ear hair.”

Miss Blake rolled her lips together very tight.

“What were you asking me?” he said mildly.

“What— Oh! The name of Professor Ogilvie’s pet monkey, sir.”

“Ah. Well, he had got over ‘Wisconsin’ and ‘Massachusetts’: heard about—? Yes,” he said as she nodded. “Shall I give you a hint?”

“Pray do.” Miss Blake helped herself to a slice of fruit-cake.

“Um... It had best be two hints. Quentin had lately become enthused on the subject of the Peruvian Indians. You may not be aware, ma’am, that many words in the Peruvian language, or such was his claim, commence with the syllable ‘qui’. For example there is the quiquina, a tree yielding a medicinal bark, and the quipu string, a means of communication in which the message is conveyed by the knotting of various coloured threads. At the same time he had become embroiled in a bitter argument with one of our most eminent Oxford theologians, who in any case was an old enemy, over the Athanasian Creed.” He eyed her blandly.

Miss Blake goggled at him.

Dr Fairbrother gave a slight cough. “The Athanasian creed, ma’am, commences with the words: ‘Quicunque vult’, and in fact is variously known as ‘The Quicunque Vu—’”

“He could not!” she gasped.

“Of course he could. I’m surprized Pansy never told you.” Dr Fairbrother ate cake. “It was a joy to hear those girls in the garden calling ‘Here, Quicunque Vult!’, I can assure you.”

“Sir, that story is apocryphal from beginning to end!” said Miss Blake roundly.

“No. ’Tisn’t,” he said simply. “Quentin was like that. Thought it a famous joke. And of course it got up the nose of his theological opponent like nobody’s business.”

“I think I’m beginning to understand why the mere exchanging of places at a girls’ school did not seem too extraordinary for those sisters to contemplate,” she acknowledged weakly.

“Thought you might be. –Watch him!” he cried as the little marmoset suddenly leapt from his shoulder, ran to Miss Blake and mounted nimbly onto her black silk knee.

Miss Blake gasped and was turned to stone.

Percival Cummings the Second made a lightning grab at the morsel of cake remaining on her plate, and retired with it to his master’s shoulder.

“Weren’t frightened, were you?” said Dr Fairbrother.

“Er—no. Just—just startled. I have never before been so close to a monkey.”

“He may come to you voluntarily once he sees you don’t scream or shrink—or refuse him cake when he tries to steal it! But I don’t force him.”

“No, of course.” The proper Miss Blake looked eagerly at the tiny figure with its entrancing feathered ears and minute hands, but the marmoset ignored her.

It was getting dark when Dr Fairbrother rose to take his leave, thanking her very much for the nuncheon, and saying he had best push on, and how far was it to Guillyford Bay?

Miss Blake looked at him weakly. “I suppose it is no more than eight miles, sir, but I doubt you will make it by nightfall. I do not think you came by carriage? At all events, I did not hear one.”

“Oh, Lor’ no, Miss Blake! Percy and I have not much truck with the trappings of gentlefolk! We took the stage to Brighton, and walked from there.”

“You took him on the common stage?” she gasped in horror.

The pleasant face crinkled into a smile. “He rode inside my coat, ma’am. I don’t think our fellow passengers realized he was there.”

“But wasn’t he terrified?”

“He was nervous at first, of course. But the sensation of body-warmth soothes him, as with all primates.”

“I see,” she said limply. “But—if you walked all the way from the town— You cannot possibly go on to Guillyford Bay tonight, sir!”

“There will be a moon, I don’t think I shall lose my way. And Percy won’t be cold, he’ll travel in his usual place.”

“You had best take the school’s trap,” said Miss Blake very firmly indeed, ringing the bell.

“I couldn’t do that: what if you need it?”

“We shan’t need it. –Pointer, please have the trap brought round immediately.”

Pointer looked a trifle startled, but bobbed and disappeared.

“The little tavern at Guillyford Bay is quite clean and respectable: you had best put up there overnight. You may return the trap tomorrow.”

“If you’re sure... Well, it will give us more time with Pansy and Delphie, won’t it, Percy?” he said, clipping the lead onto his pet’s collar again. “Any messages, Miss Blake?”

“Yes: please tell them that I shall call very soon. And—and if you could ascertain quietly, Dr Fairbrother, whether they are in want of anything, I should be grateful.”

“Aye, I’ll do that. Only I dare say they won’t be: Pansy sounded very cheerful in her letter. She said Delphie’s starting a garden,” he revealed with a smile.

“Starting a— Well, I am sure Mr Garrett will rent them the cottage as long as they wish, but do they wish to remain there for any period?”

“Pansy seemed to think that with what they had saved they could manage for some time. And with the money I’ve screwed out of old Humphrey, they’ll certainly be able to afford to stay if they want to.”

“Ye-es.. I have not yet heard from their Aunt Venetia, but I think it likely she may wish them to go to her.”

“That’s the sister that’s married to a vicar, isn’t it? Aye. Can’t remember... Quentin had his back up over some religious question or another: the brother-in-law would not give in over the point, I think.”

“Something to do with the Trinity, I think Pansy mentioned,” said Miss Blake weakly.

“Sounds likely. An original mind, you know, but dashed intransigent, Quentin. I forget what he and old Humphrey Ogilvie fell out over—something and nothing, most like.”

“Very probably,” said Miss Blake feebly, by now quite unable to recall whether she had known that Dr Ogilvie and his uncle had fallen out.

“Aye, they’re an eccentric lot! Er—talking of eccentric families, ma’am, possibly I should warn you, my sister may descend upon you.”

“Er—yes?” said Miss Blake politely.

“Portia. Lady Winnafree.”

“Yes?”

Dr Fairbrother pulled an awful face. “Of course, you probably would not have heard the name. Her husband’s a Navy man. Retired, now.”

“Good God, not Admiral Sir Chauncey Winnafree’s wife?” she cried unguardedly.

“Mm. Years older than Portia. Married her in the teeth of his family’s wishes. And Mamma’s and Papa’s, come to think of it. Know of him, do you?”

Miss Blake swallowed. “I—I used to be acquaint with—with someone who had sailed with him, sir. On the Regardless.”

“Good name for any flagship of old Chauncey’s,” said Dr Fairbrother.

“So I had understood,” she agreed weakly. “And—and you say Lady Winnafree may come here?”

“Mm. Wrote to her,” he admitted with a rueful sniff, “before I had squeezed the money out of old Humphrey. Thought the girls might need a helping hand, and Portia’s always complaining how moped she is in town with nothing to do, and last time I saw her said did I know of any pleasant girls whom she might take under her wing. Well, of course I said I didn’t. Only when Pansy wrote I thought—er—well,” he said, grinning, “I thought that being rescued by Portia might be one step better than starving in the gutter! For girls, mind. No male in his senses wouldn’t fifty times rather starve in the gutter than fall into her clutches! So I wrote her about them. Recommended she apply to you for their direction and—well, I thought you would give her a fair picture, ma’am, in the case she wanted a second opinion. Had a reply just before I left. –She makes Chauncey hire these damned fellows that eat their heads off eleven months of the year in the case her Ladyship may wish to send an urgent message that can’t be entrusted to the post. Chauncey’s Couriers, we call ’em in the family. Quite embarrassing, really, to have a liveried fellow on a steaming horse come dashing up to your doorstep and present you with something drenched in violet scent!” He laughed. The little monkey joined in, chittering excitedly.

“Ssh,” he said, stroking him gently. “You hate the violet scent, too, don’t you Percy, my pet? Mm, sweetheart? Ain’t it nasty, then? –No, well, possibly he loves it, for he ate the last letter!” he said to Miss Blake with a twinkle. “Well, be warned, Miss Blake: if Portia descends it will be in force.”

“You had better warn the Miss Ogilvies, sir, rather than myself, surely?”

“No,” Lady Winnafree’s brother explained breezily: “didn’t give her their direction; thought they might be moved on by the time Portia stirred her stumps. It always depends on whether she has an urgent appointment with some dashed mantua-maker, you see!”

“I see. We shall look forward to receiving Lady Winnafree, then.”

Dr Fairbrother merely grinned.

Pointer then announcing the trap, he shook hands with Miss Blake, thanked Pointer on behalf of himself and his pet for the delicious refreshments, and took his leave, promising to return the trap before nightfall tomorrow.

In the suddenly silent front hall, mistress and maid looked at each other limply

“Dr Fairbrother is an old friend of the Miss Ogilvies’ papa,” said Miss Blake feebly.

“Yes, Miss. So he’ll be goin’ on to see them?”

Pointer, who was a local woman, had had to know more or less the whole story; though Miss Blake very much hoped that it had not yet come to the ears of the pupils or, indeed, the other teachers, none of whom was likely to visit in the environs of Guillyford Bay. So the headmistress nodded silently.

“Yes, Miss. I hope as how Horatio Nelson don’t take to the little beast, Miss!”

“I think Dr Fairbrother will keep him on his shoulder. He—he is a man of science, Pointer. From Oxford,” she explained weakly.

Pointer replied wisely that she had thought it might be something like that. And she had brought some muffins in to Miss Warrington, she added.

“Very good, Pointer. –Oh: you mean she did not ask?”

“No, Miss Blake. Only me and Cook thought, seeing as how you and the gentleman was havin’ ’em, and it being a right nasty sort of day—”

Miss Blake swallowed a sigh. Letitia Worrington was one of those women who voluntarily martyred themselves—though for no good cause whatsoever. “You did very well indeed, Pointer. I expect—er—Miss Worrington had lost track of the time.”

Pointer eyed her tolerantly. “Yes, Miss.” She hesitated. “Miss Blake, did he sit up and drink his glass of water like a Christian?” she burst out.

The headmistress jumped slightly. “Oh: yes, he did. I wish you might have seen it, Pointer!”

“Indeed, Miss,” she agreed wistfully. “Did you remark them little hands, Miss?”

Miss Blake smiled. Very evidently Dr Fairbrother’s barometer was of the infallible kind! For there was no worthier human being upon the face of the earth than Pointer.

She agreed she had remarked the little hands, and agreed with Pointer that it was wonderful what variety of animals there was upon the earth, to be sure, and retreated to the sitting-room, smiling. Evidently Pointer had also looked to the fire, for there was a good blaze going, which there would not have been, had Miss Worrington been left to indulge her inclinations to martyrdom.

Letitia quavered out an enquiry about the monkey, and somehow Naomi Blake found herself telling her timid colleague all about the delightful feathered ears, and the way he hunched himself down into his shoulders so that it appeared he was wearing a ruff, and the tiny hands... She did not say much about Dr Fairbrother himself, for she did not wish to indicate that the Ogilvies were still in the neighbourhood. Which did not mean that he did not remain very much in her thoughts.

A very small maid in a large cap and a rumpled apron—and very flushed cheeks—opened the door of Elm-Tree Cottage to Dr Fairbrother. A strong smell of singeing meat immediately pervaded the air.

“Well, well: good evening! And who are you?” he said with a grin.

“Ratia Bellinger, sir!” she panted. “And if you please, sir, if it be Miss Delphie as you wants, she can’t come just now, acos she’s got her hands full!”

“Well, Miss Pansy would do,” he said, twinkling. “Tell her it’s Dr Fairbrother, would you, please, Ratia?”

“Yes, sir! Only Ratio Nelson, he done leave a rat in the scullery, and Miss Pansy she’s a-buryin’ of it as we speaks! Acos else, ’e might drag it off to anywheres! And Miss Pansy, she said as onct ’e left one behind her Pa’s big chair, and it didn’t ’alf start to pong!”

The derivation of Miss Bellinger’s given name was now very plain to Wynn Fairbrother: his teeth flashed in the light of Ratia’s candle and he said: “Well, I’ll go on round to the back garden to speak to her. And mayhap give her a hand with the digging: Horatio Nelson in his time has been known to disint—dig up buried rats.”

“Aye, I knows, acos ’e’ll dig like a dog if ’e gets the scent of one of ’em!” she said, chuckling.

Dr Fairbrother would have gone around to the back without more ado, but at that moment a voice called: “Ratia, pray who is it at the door?”

“It’s Wynn Fairbrother, Delphie, my dear!” he cried loudly. “May I come in?”

There was a gasp from inside, and Delphie appeared, also in a rumpled apron—though not a cap—and also very much flushed. “Dr Fairbrother! Oh, how wonderful to see you!”

Grinning, Dr Fairbrother dropped a kiss on her cheek and came in.

Naturally Delphie then burst into tears, but he competently removed from the sitting-room spit the piece of meat she had been singeing, patted her back and got her sat down.

Pansy soon appeared, rolling her sleeves down, and accompanied by Horatio Nelson Cat. The zoologist duly saluted her cheek, and told her kindly she was looking in rude health. She did not burst into tears, but then Dr Fairbrother had not expected her to.

It rapidly becoming apparent that none of the three girls was capable of singeing a piece of meat properly, Dr Fairbrother took over operations at the fire, and, Ratia Bellinger apparently being capable of setting out bread and cheese, and Delphie of making a pot of tea, they were soon sitting down to a pleasant supper. All four of them, for there was only the sitting-room plus a tiny kitchen and scullery in the downstairs part of the cottage. It was, however, quite a roomy cottage, for upstairs it had three bedrooms. Not large ones, true, but Delphie and Pansy felt themselves very well off indeed. Once Horatio Nelson had been awarded a share of the meat, for after all if rats were not highly desirable in the scullery they were certainly better dead than alive, he settled down very contentedly in his usual position on the hearth rug.

What with getting supper and the pleasure they all took in one another’s company and the news they all had to exchange—Pansy being particularly interested to hear that Dr Fairbrother had embarked upon a monograph on the learning ability of the lower primates, Delphie being vastly fascinated to learn that a Miss Squires had lately come to live with Mrs Bridlington as companion to Clara and that both Mr Smothers and young Mr Bridlington were pursuing her with earnest ardour, and the zoologist demanding to hear every detail of Pansy’s new naval occupations—it was really very late before Dr Fairbrother remembered with a start that he had something for them, and produced the bank draft.

The first shock being over—which took considerable time, and a fresh burst of tears from Delphie—Pansy naturally began to speculate upon how he had done it.

“You held a pistol to his head.”

“Wrong.”

At this point Percival Cummings the Second emerged from his coat, and Ratia gasped.

“It’s only his little pet monkey, Ratia. Hullo, Percy! Hullo, Percy!” squeaked Pansy, what time Delphie cried: “Oh, he has been hiding in there all this time! Hullo, Percy! Cheep, cheep, cheep!”

“Look at ’is little hands! Like a tiny man!” gasped Ratia.

It had been evident all along that Ratia Bellinger was the salt of the earth, so Dr Fairbrother was not surprized by this remark. Though it must be admitted he grinned to himself.

There was not much in Elm-Tree Cottage which was suitable for a monkey to eat, but once Percival Cummings the Second had been provided with a few currants and was perched on his master’s shoulder nibbling at them, Pansy continued: “You threatened to marry his housekeeper.”

“Wrong.”

“You sent for candles in his house?” suggested Delphie, smiling very much.

“Wrong!” he choked.

“You threatened to have his drive cleared and send him the bill,” was Pansy’s next suggestion.

“Wish I’d thought of it,” the zoologist admitted, grinning.

“You threatened to sic Mrs Bridlington onto him!” she squeaked, collapsing in giggles.

“No, but I grant it would have worked splendidly! Er—well, I can’t tell you how I did it: I suppose I just ranted and raved. I certainly became very loud and forthright!”

“I wish I had heard it,” said Pansy wistfully.

Delphie rather did, too, but she bit her lip a trifle guiltily.

“Ole miser that ’e be,” agreed Ratia comfortably from her warm position down by Master Horatio. “Well, so now you be set: you be two young ladies with a fortune!” She beamed upon them.

“I wouldn’t say that, precisely, Ratia. But I think we need not worry about money again,” said Delphie, sighing deeply. “Dear Dr Fairbrother, I cannot say how grateful—”

“Now don’t bawl again, Delphie!” he warned.

“I shall not,” she said, smiling and sniffing. “But you must allow me to express our thanks—”

Wynn Fairbrother replied firmly that she had already done so, and, the hour being now considerably advanced, departed for the tavern, promising he’d be along bright and early in the morning for Pansy to take him out in the Poppet.

“Huzza! I shall be able to buy Poppet for my very own!” cried Pansy as the girls retreated to the fire.

“Yes,” said Delphie with a happy sigh. “And we shall be able to purchase a nice sofa, and perhaps some rugs, and new curtains. And we must see Mr Garrett, and have a proper lease, I think!”

“Yes. And I tell you what: let’s buy Ratia a proper maid’s uniform, like Briggs or Pointer!”

Ratia beamed, as Delphie approved the scheme.

“I wish there was some way we could repay Dr Fairbrother,” said Pansy thoughtfully.

“Oh, indeed!”

They racked their brains but could think of nothing very much that could possibly repay his kindness. Helpfully Ratia suggested a pot of her ma’s rhubarb preserve. The young ladies agreed eagerly, even though this would rather deplete their store-cupboard of its best delicacy. What Mrs Bellinger put it in besides the rhubarb they knew not, but it was a miraculous concoction.

“Imagine,” said Delphie ecstatically: “no monetary worries for the rest of our lives!”

“Yes: you need not take any position Miss Blake finds for you,” said Pansy pleasedly.

“Thank goodness!” said Delphie with a guilty smile. “I was dreading having to go off by myself to live with a strange family!”

At this the gruff sea-captain, though not given to gratuitous gestures of affection, heartily embraced her.

“Aye,” said Ratia Bellinger with great satisfaction: “it do seem to be workin’ out as if it was Meant!”

Next chapter:

https://theogilvieconnection.blogspot.com/2022/09/the-parkers-in-london.html

No comments:

Post a Comment