31

Return To Guillyford Place

A damned odd mixture of guests had assembled at Guillyford Place for the wedding of Felicity Tarlington and Rupert Narrowmine. At least, Wynn Fairbrother had declared the mixture to be so, pointing out that Lady Tarlington did not know what to make of himself let alone Percy, though she had bravely mentioned Lady Georgina Claveringham in that context; that Sir Gerald’s exclusive concentration on the two topics of his own health and the exaggerated reputation of the waters of Leamington Spa would, he feared, strike anyone outside the immediate family as odd, given the occasion; that Lady May Claveringham appeared to be here without her mother’s knowledge and he only hoped the Countess of Hubbel never latched onto that one; and that if that old hag with the lorgnette wondered once more in his hearing that Lady Blefford should care to desert her husband when his health was so uncertain, he would very probably strangle her with his own hands.

“Oh, he’s missed the point entirely, poor fellow,” noted Mr Tarlington, shaking his head.

“Aye!” choked Lord Rupert, going into a paroxysm.

“That’s Aunt Hubert Narrowmine, Dr Fairbrother,” explained Alfreda kindly. Her lapis eyes twinkled. “Both she and her husband dislike Lady Blefford intensely.”

“You could say that!” choked Rupert. “And neither of ’em can stand Papa, what’s more!”

“But— Oh,” said Dr Fairbrother, grinning sheepishly.

“And Lady May has been staying with her sister; I think her Mamma can hardly be unaware of that,” added Alfreda gamely.

It was true that Lady May had been permitted to visit with Lady Jane and Commander Carey until the coming Season—yes. Whether Lady Hubbel was aware that the Careys had been invited to the Narrowmine-Tarlington wedding was another matter entirely. As was the point that, Fliss having kindly invited May to come to the Place for the two weeks before the wedding, May had eagerly accepted. Dr Fairbrother eyed Lady Harpingdon drily, but did not mention these matters. Nor the closely associated point that Theo Parker had now been at the Place for ten days.

“Well,” he said, getting up and stretching, “think I’ll go and hide in the billiards room.”

“You can’t. Well, you can, only Harpy and Harley Quayle-Sturt is already hidin’ in there,” explained Lord Rupert. “Think young Ludo Parker might be with ’em.”

“Good: I’ll join them,” said the zoologist, going out.

Lord Rupert looked after him wistfully.

Alfreda rose. “Rupert, my dear, I do not think anyone would mind if you joined the gentlemen in the billiards room.”

“Mamma’s ordered me to keep an eye on Uncle Hubert,” he revealed glumly.

“He is sitting quietly with Sir Gerald in the pink salon,” replied Alfreda composedly. “They are exchanging reminiscences of their youth.”

Lord Rupert winced slightly, but nodded. “Then where is Aunt Hubert, Alfreda?”

“She, Mamma and the girls are looking over Fliss’s trousseau.”

“Again? Oh, well, good,” he recognised. “Um—well, if you think it’s all right, I might just cut along.” He gave her a plaintive, pleading look.

“Yes, go,” she said kindly.

Rupert escaped thankfully.

“What’s he supposed to be stoppin’ Lady Hubert from doin’, Cousin Alfreda?” drawled Mr Tarlington. “I grasp that he’s supposed to be stoppin’ Lord Hubert from losin’ the family fortunes at play, but—”

“Do not be silly. Lady Blefford is afraid that Lady Hubert may speak unreservedly of family matters to your mamma. Or to mine.”

Mr Tarlington grinned. “Thought she only did that after the half bottle?”

Alfreda replied composedly: “Very like. The housekeeper at Blefford Park has informed me, however, that there is generally an opened bottle in her room.”

Mr Tarlington choked, but managed to say: “Speakin’ of talkin’ unreservedly of family matters!”

Alfreda’s eyes twinkled, but she merely said: “I am going upstairs to check on the twins and the little ones. Please excuse me, Cousin Aden.”

“No, I’ll come with you,” he said immediately.

“I think your mamma believes you to be—um—keeping an eye on your Uncle William Tarlington and Mr Vernon Mainwaring,” she murmured.

Mr Tarlington replied brutally: “If Uncle William hasn’t learned by now not to play cards with old Cousin Vernon, then at his age there’s no hope for him! Come on.” He offered her his arm: Alfreda took it, smiling, and they went out.

“It could be worse,” he said kindly on the stairs.

“How?” replied Alfreda frankly.

Choking slightly, Mr Tarlington explained: “Old Great-Aunt Hetty Charteris-Brown could be here.”

“Er—Christian has an elderly relative who steals the silver,” she offered.

“Really? Don’t think I’ve ever met that one,” he said with interest. “Though I’ve met Rockingham’s: old Peregrine Jerningham. Reputed to have had a glove of chain mail out of the—”

“Great Hall at Daynesford Place: yes, so I have heard,” she said composedly.

“It’s the sort of family secret that the whole of Society knows,” he admitted. “But Great-Aunt Hetty don’t steal the silver.”

Alfreda eyed him suspiciously.

“She sets fire to things,” said Mr Tarlington dreamily. “Houses, mostly. Though in summer, she’s been known to favour a barn or a rick or two.”

Alfreda gulped. “I really find it hard to believe that.”

“You would not, if you lived in Kent,” said Mr Tarlington simply.

Alfreda gulped again.

In the hastily re-opened Guillyford Place schoolroom, Miss Henrietta Parker was discovered, helping Lucy with her sums.

“Thought you said the girls was lookin’ at Fliss’s trousseau, Cousin Alfreda?” said Mr Tarlington.

Henry had gone very red. “Dimity and May are.”

“Then why aren’t you with ’em?” he said, frowning.

“I’m sorry, Cousin, but I could not take it any more,” said Henry with a sigh. “I know I’m supposed to—to be one of the house party—”

“No, it’s all right,” he said quickly. “Come on, we’ll go for a w— Wait. Where, may I enquire, is Miss Fletcher?”

Henry looked at him nervously. Miss Fletcher was an elderly lady who had once been his little brothers’ governess: she had come out of retirement at Lady Tarlington’s urgent request. Mr Tarlington had earlier pointed out that she was incapable of making a child of two mind her. “Pray don’t be angry, Cousin Aden. She has a headache, so I said I would keep an eye on the children.”

“I’ll take over now, Henry, dear,” said Alfreda quickly. “It will be time for their midday meal soon, in any case.”

“Um, well, thank you,” said Henry, eyeing their cousin uneasily. “The twins are doing a piece on the geography of Canada. What I mean is, first they had to draw a map, and now they are writing about the characteristics of the country. Um—Miss Fletcher set it.”

“Good,” said Alfreda mildly. “And Lucy?”

“Um—well, I set her some sums, but—”

“They are TOO HARD!” shouted Lucy suddenly, turning puce. “And I AM NOT stupid! And I NEVER had subtractions, see!”

“Ooh!” cried Charlotte indignantly, looking up from the geography. “Lucy Parker, what a bouncer! Miss Drayton—”

“That’ll do,” said Mr Tarlington grimly.

“But Cousin Aden, she’s done subtraction with Miss Dr—”

“I said, that’ll do. And Lucy, if I find you have been telling bouncers, I’ll put you over my knee.”

“I’m ONLY LITTLE!” she cried. “And I NEVER had subtractions!” She burst into loud tears.

“Lucy,” said Lady Harpingdon coolly: “stop that this instant. No-one is impressed. And Charlotte, whatever the provocation, one does not tell tales, and especially not of persons younger than oneself. Lucy’s lie would have been discovered, in time.”

“I’M NOT LYING!” she screamed, throwing herself to the floor and kicking madly.

Mr Tarlington watched in a bemused fashion as Lady Harpingdon, calmly picking her kicking and screaming little sister up, carried her out bodily.

“I’m sorry,” said Henry limply. “She’s over-excited. And I have to admit she behaves very badly when she’s caught out in a lie. And—um—I think over the past year Papa has let her get away with—with more than he realised he was doing.”

“Yes,” said Mr Tarlington numbly.

“Um—family life is like that, I’m afraid,” she said, biting her lip. “I hope you did not think that Lucy is—is sweet all the time.”

“She isn’t,” said Charlotte briefly.

“No, she isn’t,” agreed Veronica loyally.

“Look, get on with your damned geography!” said Mr Tarlington heatedly. “Uh—look, will they?” he muttered.

“Yes; the Narrowmine twins are utterly trustworthy,” replied Henry calmly.

Charlotte and Veronica were observed to turn puce and swell up proudly. They buried themselves in the geography.

“I’m a good boy,” said Daniel into the utter silence.

“U,S,U,A,L,L,Y,” clarified Henry.

“Mm. Uh—well, shall we go for a walk?”

“Um—well, yes... Um—well, it’s true that Daniel has been very good this morning…”

“Very well. Come along, Daniel, you and Henrietta and I will take a walk,” said Mr Tarlington.

Daniel scrambled down from the table, beaming. “I did sums,” he said confidentially, taking Mr Tarlington’s hand.

“Really?” replied Aden weakly, avoiding Henry’s eye.

“Two and three are five!” said Daniel proudly.

“Very good,” said his big cousin feebly.

If Mr Tarlington had had any specific expectations of this walk, they were not to be fulfilled. Daniel chattered incessantly, and Henrietta was very silent.

Eventually, as the little boy ran upstairs on their return, Mr Tarlington, assisting Henrietta out of her heavy cloak, said stiffly: “Were you bored?”

“No,” returned Henry blankly.

“Oh. You did not say very much.”

“Didn’t I?” she replied feebly.

“I thought perhaps,” said Aden in spite of himself, “that you were comparing a very boring stroll in the very boring grounds of Guillyford Place in very boring company, with some of the rather more exciting and exotic strolls you must have taken this past year, in places like Paris or Rome or Venice.”

“One does not actually stroll, in a gondola.”

“General Ramsay said—” Aden broke off, biting his lip.

“Whuh-what?” she gulped.

“He mentioned St Mark’s Square,” said Aden, clenching his fists.

“What? Oh, the Piazza San Marco! Yes. Um—that was a very hot day. Actually, it was stiflingly hot all the time we were in Venice.”

“Indeed?”

“He—he was very kind to me,” said Henry in a tiny, trembling voice. “Like a—an uncle.”

Aden swallowed hard. “Yes. Of course he was. –I’m sorry,” he said in a low voice.

Henry might have said something, though at the precise moment she could not think what, but Lord Rupert wandered out into the hall with a billiard cue in his hand, saying loudly: “Thank God: you’re back! Maybe they’ll give us some food, at last!” And the moment was lost.

It was all pretty much like that, Aden discovered gloomily as the date of his sister’s wedding drew nigh and he had still not managed to see Henrietta alone for more than two minutes at a stretch. What with that and the selection of batty old relatives on both sides... Not that he’d expected anything more, he kept telling himself. And at least Ramsay had indicated that his cousin was not indifferent to him. But if only he could get her alone!

Henry herself was a prey to mixed feelings. She did not know whether she wished more to be alone quietly with Cousin Aden, or to avoid a tête-à-tête.

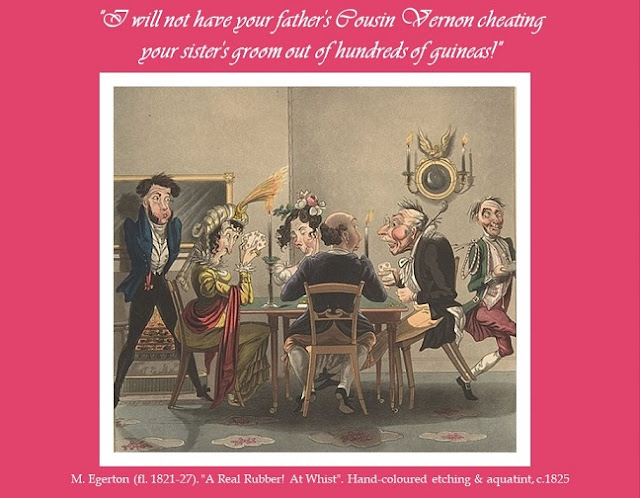

The evenings of the week immediately preceding the wedding were enlivened by lottery tickets and spillikins for the younger persons, and cards for their elders. Aden’s mamma had ordered him, there was no other word for it, to keep Lord Hubert Narrowmine and Cousin Vernon Mainwaring occupied at cards, and on no account to let his Uncle William Tarlington join them, they did not need a bankruptcy in the family. Aden had pointed out that in that case, it would have to be whist, which Cousin Vernon did not care for. Though it was true he cheated at it, too. But unfortunately it required four players.

“Then your father may play, and I do not care if he drops a fortune!” she snapped.

“Well, I care, ma’am, it’ll be my fortune.”

“Show some initiative, Aden!” snapped his mother.

Aden blinked: lack of initiative was not something of which Lady Tarlington had hitherto accused him. “Initiative. Very well. But I don’t think initiative is going to stop old Cousin Vernon from cheating, whatever game we choose.”

“It had better,” she warned.

“Possibly Rupert had best make up the four: he has been ordered to see old Hubert don’t drop a fortune,” he drawled.

“I will not have your father’s Cousin Vernon cheating your sister’s groom out of hundreds of guineas!” she screamed.

“Er—no, that’s a point. Um—do it have to be cards, ma’am?”

“Do you have a better suggestion?” she snapped.

“Uh—charades?” he groped.

“At their ages? Do not be absurd!”

“No—uh—thought they could be the audience.”

“You are being ridiculous, Aden: I do not wish to have my salon filled with an assortment of elderly oddities in the state of crochety boredom customary in those who are forced to be the audience for younger persons’ charades, while they wait interminably for the next scene!”

Aden opened his mouth feebly—largely in admiration of her turn of phrase: but he was not given the chance to express this.

“And may I remind you, while you are struggling with the men, I shall have to cope with Celia Blefford, Lady Hubert, and Mrs Parker!”

Mr Tarlington went rather red. “Mrs Parker cannot by any stretch of the imagination be labelled an elderly oddity, ma’am.”

“She doesn’t play whist!” she snapped.

Ouch. Mr Tarlington gulped, promised his mamma that whether it were écarté or whist or something else entirely, he would keep the elderly male oddities amused, and retreated.

... “I have only been to Bath the once, when my cousin Delphie was married,” admitted Henrietta.

“Oh, yes? Poor sort of a place. Pretty, y’know. Handsome houses. Demned dull, though. Shockin’ waters. Never did me a bit of good.” Sir Gerald Tarlington shook his head sadly.

“Really? I’m sorry to hear that, sir. I had heard the Bath waters were famed for their curative properties.”

“Aye, well, so had I, or I would never have gone near the place. Now, take this leg of mine: you would not believe the agonies I have with it!” he said proudly. “Damned doctor’s told me a load of cock and bull, too. Never believe a word a doctor says to you, me dear, he has his eyes on your guineas,” he warned.

“Oh,” said Henry feebly. Unfortunately Sir Gerald seemed to expect more than that as an answer. “I—I shall be very wary of doctors in future, sir.”

Very pleased, Sir Gerry patted her knee and told her a very long, boring story about his leg.

Pansy, meanwhile, had been cornered by Uncle William Tarlington. In his youth, a fair time back, Uncle William had been a Naval man. Pansy’s face brightened. She began to ask him about Lord Nelson, and the great sea battles. Uncle William Tarlington informed her that that was dull stuff for a pretty little lady like herself to be bothering her head with, and had no-one ever told her, she had quite a look of Lady Hamilton? An expression of anguished disbelief gradually spread over Pansy’s face as, edging up rather too close to her on their little sofa, old Mr Tarlington told her a very, very long and what turned out to be a completely pointless story that involved himself, the Med., Lord Nelson—peripherally—Admiral Dauntry as a young man, Lady Hamilton—peripherally—and a very pretty young lady who had been some sort of distant connexion of Sir William Hamilton’s.

“Poor Pansy,” murmured Fliss.

“Well, yes,” agreed Alfreda.

“But at the least while he’s boring her to death, he isn’t losing a fortune at cards!” added Fliss cheerfully.

… “Game of billiards, Wynn?” said Mr Quayle-Sturt kindly.

“Harley, old man, there’s only so much billiards a man can take!”

“Piquet?”

“No money,” said the zoologist simply.

Mr Quayle-Sturt offered equally simply: “We could play for nuts.”

“We could, aye. Only have you got any?”

“No, I am afraid you will have to advance me a handful,” he said tranquilly.

Grinning, Dr Fairbrother produced a handful of nuts from his pocket, and the two sat down to piquet.

“I have to admit,” said the zoologist, having rescued Pansy from the clutches, once again, of Mr William Tarlington, “that I’d forgotten how bad this sort of thing is.”

Pansy nodded feelingly.

“Well, Portia and Chauncey are due tomorrow: they may brighten things up.”

“Certainly: Sir Chauncey and Mr William Tarlington will be enabled to sit in a corner exchanging reminiscences of Lady Hamilton and Mirabelle Coulton-Whassett!”

“Something like that: aye!” he choked.

Pansy smiled but said: “We did know it would be bad.”

“Mm.” He rubbed his nose. “Could get out of it tomorrow? Nip down to Guillyford Bay and get out in the Poppet?”

Pansy sighed. “No, I have absolutely promised Aunt Venetia to be entirely good and proper.”

Dr Fairbrother groaned.

“There is nothing to stop you getting out of it.”

“Er—well, no: as a matter of fact I have absolutely promised Naomi to be entirely good and proper.”

Pansy choked slightly, but said with an anxious look in her eye: “Or?”

“Or,” said Wynn Fairbrother with a twinkle, “she will not after all marry me in three weeks’ time.”

Pansy gasped, and clapped her hands.

“Ssh!” he said, grinning. “We don’t want a damned fuss like this one.”

“No. –It is definite that that will be the date, then?”

“Aye. No idea what you said to her, but it did the trick.”

Blushing, Pansy explained: “I—I just said that you were very miserable without her.”

“Oh? Didn’t try to tell her that life is not all cut and dried, or something of the sort? No helping of common sense? No rational arguments put forward?“

“No. I—I did not advance any arguments at all.”

Dr Fairbrother suddenly put his hand over one of hers and squeezed it very hard. “Thanks.”

Pansy smiled shakily, and squeezed his hand back.

“That man,” said Lady Tarlington in a lowered voice, “is extremely odd, Venetia.”

“Er—well, yes. But—um—an estimable character; Theo and Simeon think very highly of him.”

“But he keeps nuts in his pocket!” she hissed.

“Mm. And the occasional monkey,” admitted Mrs Parker with a twinkle in her eye.

“Quite.” Lady Tarlington watched in dismay as her guest played a card. “Venetia, my dear, have you never played piquet before?”

“Oh, yes: Simeon taught me, many years ago,” she replied happily. “Was that wrong, Lettice?”

“Er—injudicious,” said Lady Tarlington limply.

“Oh, well—!” Mrs Parker took the card back. Lady Tarlington swallowed.

“But of course I have not played for many years: we are usually far too busy for cards at home!” she added happily.

“Er—yes.” Lady Tarlington played a card. “I confess,” she said with a sigh, “I have not managed to work out how Fliss met him.”

“Dr Fairbrother? Well, it was when she and Aden were in Oxford, looking after Delphie and Pansy.”

“I see,” lied Lady Tarlington gamely.

They played on, an expression of dismay gradually overspreading her Ladyship’s thin, acidulated features.

Eventually Mrs Parker said happily: “Lettice, my dear, I do not think I can move, shall I concede the game?”

“But—” Lady Tarlington took a deep breath, nodded and smiled nicely, and rang for the tea-tray.

... “Er—sorry, Rupert,” said Mr Tarlington awkwardly when, all the younger ladies and the male and female elderly oddities having taken themselves up to bed, a handful of the younger gentlemen were fortifying their nerves in the library.

“Eh?”

“For celebrating your nuptials by filling his Papa’s house with dotty old relatives, I think he means,” said Christian smoothly, passing him a glass. “Drink up, dear fellow.”

Rupert accepted the glass but said: “Oh, is that all! Lor’, don’t regard it, Aden. You never saw such a collection of quizzes as we had at Blefford Park for Harpy’s!”

“Exactly!” agreed Christian, laughing. “Well, Aden, what is the plan for tomorrow?”

Mr Tarlington passed his hand over his forehead. “Let’s see. You are deputed to keep your Uncle Hubert off the cards—and now I come to think of it, off the brandy, too: Papa has been lookin’ at the decanters and mutterin’ under his breath.”

The Narrowmine brothers and Mr Quayle-Sturt choked; Ludo Parker went into a spluttering fit.

“No, well, sorry. Thought we might take the guns out.”

“Good,” said Rupert frankly.

“That is,” his cousin added kindly, “if you feel you should be deserting your fiancée at such a time.”

“Deserting her! I can’t damned well get near her! When they ain’t closeted in her room spreading out the trousseau, or counting damned hideous presents in the little morning room, they’re sitting in corners yattering about dashed dresses!”

“They’re all like that,” agreed Ludo.

“Yes, well, I’m with you. Shootin’ it is. And tell ’em to pack us a decent meal, we’ll stay out all day,” ordered the groom on a sour note.

Mr Tarlington’s shoulders shook slightly, but as he raised no objection to this plan, the gentlemen concluded thankfully that he was in full agreement with it.

... “But where are they?” cried Fliss aggrievedly.

“I believe they took the guns out,” said Henry on a dry note.

“What? You cannot mean they intend staying out all day!”

It was a fine, crisp March day: very windy and not warm, but there was a pale blue sky and a lot of high, fast-moving cloud. “Can I not?” returned Henry.

“This is beyond everything! And never tell me that Cousin Christian has gone, too!”

“Mm,” Henry admitted, avoiding Alfreda’s eye.

“And—and Mr Quayle-Sturt?” she gasped.

“He is absolutely sure to have gone!” said Lady Sarah with a laugh.

“I would never have believed it of him, Sarah!” cried Fliss bitterly.

“Er, well,” said Henry uneasily, “it is apparently just the day for it.”

Dimity took a deep breath. “Henry, did—”

“Yes,” said Henry succinctly.

“That is gentlemen all over!” she declared.

Very flushed and cross, the bride agreed.

At luncheon it was discovered that Commander Carey must also have accompanied the shooting party. Well, he was certainly not at the luncheon table. The young ladies looked at Lady Jane.

“He is quite a fair shot, even with his one eye and his stiff arm,” she said placidly.

“But Jane, are you not cross? They have deserted us!” cried Fliss.

Lady Jane put her head on one side. “Not cross, no.”

“Only got yourselves to blame. The lot of you have been huddled in corners over damned linen and gowns and stuff for weeks on end,” said Sir Gerald unexpectedly.

“Gerry! Really!” snapped his wife.

Sir Gerald shrugged.

“You are in the right of it, of course, sir!” admitted Henry with a little laugh. “The poor gentlemen have been feeling excluded from the proceedings, I fear!”

He smiled pleasedly, and nodded.

... “I like that little Henry girl,” he said to his wife, later that day.

“Do you, indeed? That is just as well, for I very much fear Aden intends to make her the mother of your grandchildren!” she retorted bitterly.

“Good.”

“Gerry, the Parkers are nobodies!”

“Uh—yes. True. Pity in a way it ain’t the one with the fortune. Brainless little thing, though: Aden don’t like that.”

“You are impossible,” she said grimly.

“I’d rather see him happy...” he said vaguely. “Funny, y’know: can’t tell why, but I keep thinkin’ of poor Vernon, lately. Must be the weddin’ or somethin’.”

“Rubbish!” snapped Lady Tarlington with angry tears in her eyes.

“I’d like to see Aden happy,” he said simply.

“I— Well, yes, so would I. But with a girl of his own station in life, Gerry!”

“He’s gettin’ on, y’know. Forty on the horizon.”

“Nonsense,” she said in a shaken voice.

“Think about it,” he advised, wandering out.

Lady Tarlington sat there, very shaken, for quite some time. Thinking about it.

“But naturally!” said Mrs Parker with an airy laugh, avoiding her niece’s eye, as Guillyford Place’s last lot of guests for the Narrowmine-Tarlington wedding, Sir Chauncey Winnafree’s party, were shown upstairs. “After all, his brother and Dimity are to be married in May!”

Lord Lavery’s brother’s being engaged to Fliss’s distant cousin did not seem to Pansy a sufficient reason for his Lordship’s forming one of the party for the wedding, but she did not say so to Aunt Venetia: it would have been a waste of breath. It could not, however, have been said that the subject could have been considered to have been changed, exactly, for, smiling happily, Mrs Parker plunged into a discussion of what precisely her niece should wear at, firstly, the dinner and ball for the neighbourhood to be held this very evening, and secondly, the wedding itself.

… “I dare say,” noted the sapient Dr Fairbrother with a twinkle in his eye when the dancing was over and the last of the revellers, not excluding the groom, had been poured into their beds or, if not forming part of the house party, their coaches, “that possibly two young ladies of our acquaintance might consider this evening to have been one of the most embarrassing of their entire existence.”

Mr Quayle-Sturt and Mr Tarlington, to whom this remark was addressed, promptly collapsed in splutters.

The zoologist produced a nut from his pocket. “Mind you, I wouldn’t contradict anyone who was to say that the pair of ’em deserved it.”

Mr Quayle-Sturt shot a look at Aden’s face, but as that gentleman immediately collapsed in renewed splutters, gasping: “Yes! If anyone can be said to deserve having Papa’s full weight comin’ down upon their toes, poor angel!” he allowed himself to collapse, also.

The zoologist merely winked, and ate his nut.

The ball had officially commenced with Sir Gerald’s inviting Lady Blefford to dance, and Sir Chauncey’s leading out Lady Tarlington. Most of those present might have been excused for thinking that once the owner of Guillyford Place had done his duty by Lord Rupert’s mamma, his bad leg would have been more than a sufficient excuse for his deserting the ballroom. And the Admiral’s age and figure for his ditto.

This did not in fact happen. What did happen was that Sir Gerald, wheezing slightly, walked up to Henry immediately the first dance was over and announced cheerily: “Dare say you will not mind takin’ pity on an old man, and sitting this one out with me, hey? –Go away, Aden: you have the rest of your life to dance with little Henrietta,” he added as his son approached. He sat down beside her and took her hand between both his own. “They tell me you know a lot about pigs,” he said complacently.

“No!” gasped Henry, goggling at Mr Tarlington.

“Now, at Guillyford we have always favoured the Yorkshire White—the larger pig, y’know, can’t be doin’ with those small, runtish ones—though I can’t claim to be much of an expert meself. –Get off, Aden, Miss Henrietta is talkin’ to me!” he said testily.

“Permit me to say, Papa, that the boot appears to be on the other foot. –He does know quite a lot about the large Yorkshire Whites,” he said to Henry. “They are a reliable breed, though some maintain that the meat is flavourless.”

“Rubbish, Aden, there is nothing like a well-cured ham from your Yorkshire White! Get off, ask your mother-in-la—um, aunt, to dance.”

Henry was now a glowing purple. She goggled from Sir Gerald to his son in dismay.

“If, as I collect you do, you mean Mrs Parker, sir, I should be happy to,” said Aden politely. He bowed, and retreated to Mrs Parker’s side.

Henry goggled in a mesmerized way at Sir Gerald. The baronet, however—though looking remarkably pleased with himself as he did so—merely chatted about pigs.

Worse, however, was to come. Sir Gerald had retreated at last and was to be seen amongst a group of his cronies, Mrs Parker was safely absorbed in chat with Lady Jane and Lady Sarah while, possibly not entirely a coincidence, Theo whirled in the figures with Lady May, and Mr Tarlington was talking and laughing with Lord Rupert and some of their gentlemen friends. Henry crept off to Alfreda’s side.

“Don’t speak, Alfreda,” she said as her sister opened her mouth.

“My love, I fear I may burst if I do not!” replied Alfreda with a gurgle. “It is clear to all of us, of course, that Sir Gerald very much likes you, but what on earth was he talking of for so long?”

Henry took a deep breath. “Largely, pigs. It seems, although in general farming does not interest him, that he knows—” She stopped; Alfreda had collapsed in muffled hysterics.

Henry sat there grimly silent.

Eventually Alfreda recovered, blew her nose, and said weakly: “My dear, surely it is preferable to having his family dislike you?”

Henry just sat there grimly silent.

Fliss and May had both joined them, Lord Rupert had separated himself from his cronies and joined them also, and Theo had also joined their group, when their hostess, horribly grand in a deep umber satin and the family diamonds—impressin’ the neighbourhood, as Sir Gerald had kindly explained to the red-faced Henrietta—sailed up to them. “Well, you are all very merry, my dears!” she said graciously as the gentlemen hurriedly rose. “Rupert, dear boy, if you speak to the musicians I am quite sure they will play a waltz for you.”

Lord Rupert had not expressed any desire for a waltz and to his knowledge he had never even expressed a liking for the waltz in Lady Tarlington’s hearing, but he hurried off obediently.

“I am quite sure that one waltz could not be thought ineligible, Mr Parker,” said her Ladyship archly as the music struck up.

Meekly Theo led Lady May onto the floor.

“Off you go, my dear!” added her Ladyship brightly to her daughter as Rupert returned.

Giggling, Fliss took his hand and pulled him onto the floor. That left Lady Tarlington, Alfreda, and Henry.

Under the horrified Henry’s starting eyes her traitorous sister rose, smiled vaguely, excused herself vaguely, and wandered off, looking vague.

“I have always said that our dear Alfreda is the soul of tact,” allowed Lady Tarlington, sinking onto the chair she had just vacated.

Henry looked at her numbly.

“I hope you are enjoying yourself, my dear? Of course, it is not Paris or Rome,” said her Ladyship with a sigh.

“It is a delightful party, Lady Tarlington,” replied Henrietta politely.

Her Ladyship sighed again. “Being a hostess is not easy.”

“I am sure,” croaked Henry, wondering wildly if that was some sort of veiled warning, intended to indicate that she, Henry Parker, would never be capable of playing hostess at Guillyford Place.

Sir Gerald was at this moment joining his son’s group, where, although admittedly Mr Tarlington did not look particularly encouraging, he proceeded to sling an arm round his shoulders, leaning on him heavily. At this point Henry consciously registered that Sir Gerald did not have his silver-knobbed stick with him. She blinked slightly.

Lady Tarlington gave the pair an evil look. “Gentlemen, of course, are useless when it comes to anything practical to do with one’s entertainments.”

“Well, yes, even in our rural fastness I had noticed that,” agreed Henry.

“Of course, my dear,” she sighed, patting her hand. Henry with difficulty repressed a jump. She smiled weakly.

“That gown is exquisite, my dear.”

“Thank you, Lady Tarlington,” croaked Henry, turning all colours of the rainbow and now not knowing what to think. Could he—could he have spoken to his mamma? Help. But he had not even said anything to herself, yet, and— Oh, dear!

Her Ladyship then told Henry a long, rambling and sufficiently bitter story about the first dinner party she had given for Sir Gerry at the town house. Fortunately she did not seem to expect any response other than a few murmurs.

“But if he had stayed home he would not have been of any assistance, you can be sure!” she finished on an angry note.

“Well, no. Mamma usually tries to send Papa out for the day, if she is to give a little dinner,” murmured Henry.

Her Ladyship gave a short laugh. “Exactly! –Mind you, he has taste,” she added sourly. Sir Gerald appeared now to be entertaining Aden’s friends—at least, he was talking expansively and they were listening politely. Mr Tarlington was still with them, but even from across the room he looked very bored.

“Er—oh: Sir Gerald? I am sure,” said Henry limply.

“He was as slim as Aden, as a young man. In those days it was still de rigueur to wear satin coats in the evening. And wigs, though Gerry did not need to: he had a delightful head of hair. Vernon’s was the same: fair, rather like Fliss’s in colour, and very thick. Aden takes after my side of the family,” said her Ladyship, looking at him sourly.

This fact had just consciously dawned on Henrietta: she nodded numbly. That rather dark, narrow-jawed face: yes, he was very like his mother. And her hair must once have been as dark as his.

“Though I was considered a belle in my day!” added her Ladyship with an unamused laugh.

Henry could now see, though she could not see precisely why, that Lady Tarlington was very unhappy. “Yes; Sir Gerald has shown me the portrait upstairs: you were much prettier than Fliss.”

“He had that taken on our marriage... Oh, well. I suppose you will say I looked a guy,” said her Ladyship on a discontented note, smoothing at her gown.

Henry returned firmly: “No, I think that fashion of doing the hair suited you. And the dress is a delightful shade. I wish I could wear such dusky red shades.”

“You flatter me, my dear.” Lady Tarlington twisted the large ruby ring on her left hand. “Gerry chose this. It is not a family jewel.”

“I noticed it in the portrait,” agreed Henry, smiling.

“Yes. –His papa let us have the Dower House, and in those days he was very interested in gardening. But he could not get quite this dark ruby shade in a rose and after some years became very disillusioned with the whole thing. But we were happy enough. Though he was already gambling. Then his papa died and— I suppose it would have been the same, in any case... The next boy after Aden died,” said her Ladyship abruptly.

Henry gulped. “I—I see. I’m very sorry, Lady Tarlington.”

“You cannot see, my dear, for you are not a mother,” she said heavily. “He was another fair boy, very like Vernon. I cannot tell you why, but Gerry doated on him. He was three when he died from a croup. After that Gerry never took much interest in the rest of them.” She sighed.

“I—I think my papa would say,” said Henry, very much shaken, “that sometimes a deep disappointment will—will have that effect.”

“Yes,” she said flatly.

There was a slight silence.

“Lady Tarlington, pray forgive me, but is anything the matter?” said Henry, taking her courage in both hands.

“The matter? No, my dear Henrietta, nothing is the matter, precisely.” She shrugged. “Except that, plan as we might, nothing ever turns out as we expect. But that is a lesson you are too young to have learned.”

Henry licked her lips nervously and did not know what to say.

“Aden’s father reminded me just the other day that his fortieth birthday is just over the horizon,” she said tightly.

“But he is not that—” Henry broke off abruptly.

“My dear child, he is that old, we are all that old, and there is no sense in repining over spilt milk,” said her Ladyship acidly. She directed a hard look at Fliss and Rupert, whirling in each other’s arms. “Not to say over Fliss’s marrying her idiot of a cousin. You may say they are well suited, and I would be the last to disagree with you, but there is every chance their children will be perfect imbeciles!”

After a moment Henry said in her most sensible voice: “They are but second cousins, after all. There is certainly a case of married cousins in our village whose children are little better than imbeciles, but that is a case of generations of in-breeding of the two families. I don’t think Fliss and Lord Rupert are in the same case, at all.”

“At least you are not claiming that either of them is possessed of any remarkable intelligence,” said Fliss’s mother bitterly.

“No; I should never claim that,” returned Henry steadily. “But I think he is good-natured and kind-hearted enough always to treat her well. And if Fliss is treated well I think she will manage to be happy and content.”

“Starry-eyed,” said Lady Tarlington with a deep sigh.

“That is natural, just at the moment,” replied Henry firmly. “But she is also taking a great deal of interest in the practical details of furnishing his house, and so forth.”

“Yes, well, I dare say she will be as happy with him as with another,” she said with a shrug.

“Happier, I think. After all, he is Lord Harpingdon’s brother. Their minds are not equal, I do not claim that, but there is something of the same… sweetness, I think,” said Henry, narrowing her eyes over it, “in both their natures.”

“Sweetness!” said Lady Tarlington with a startled laugh.

“Yes,” said Henry firmly.

Her Ladyship thought about it. “I am sure I hope you may be right.”

Henry’s eyes twinkled, just a little. “It is not every man who would promise his bride a pair of parrots as a wedding gift.”

“No: ridiculous,” she murmured, her lips twitching reluctantly.

“There you are, then,” said Henry firmly.

“Yes. –Gerry is right, you are quite a clever little thing. You are lucky that your papa permitted you an education. Mine was firmly of the opinion that girls do better with completely empty heads.” She looked bleakly at the dancers.

“Lady Tarlington,” said Henry, clearing her throat, “if you have been trying to tell me that—that cousins should not marry and that—that you do not want another disappointment with your children and—and that in any case I am too young for Mr Tarlington, then—then pray believe that I have no wish to bring any further disappointments into your life. He—he has not spoken to me and—and if it means so much to you,” she said bravely, blinking back tears, “I shall tell him that it is impossible, if—if he should.”

Lady Tarlington sighed heavily. “No, you absurd child. If I am trying to tell you anything, it is that you had best have him, and get what happiness you both may.” She got up. “While,” she added on a dry note worthy of Mr Tarlington himself, “Sir Gerry is still around to enjoy the spectacle of his grandchildren at his knee.”

She rustled away while Henrietta was still sitting there with her mouth open in stupefaction.

Sir Chauncey, meanwhile, had approached Pansy after his dance with Lady Tarlington. “Supposin’ you was to take a turn on this old sailor’s arm, hey? And then we might hop the next, what do you say?”

Pansy perforce rose, took his arm, and strolled slowly round the ballroom with him. The Admiral took the opportunity to pass on his captain’s report of the yacht, being refitted in her winter quarters, and Pansy foolishly concluded that she was safe.

“Only a country dance; dare say we might essay it nonetheless, hey?” said the old man as the next tune struck up.

“If you wish, of course, sir; but—um—my Aunt Venetia is without a partner, possibly you should rather dance it with her?”

“Possibly I should, aye. Thing is, the woman is a hen. Pretty enough, but not a thing in her head but receets and babies. Well, and possibly weddings, I’ll grant you that. Sort of female I’ve managed pretty successfully to avoid all me life!” he concluded with his wheezy laugh.

“Er—yes,” said Pansy, rather shaken. Sir Chauncey could of course be quite outspoken, but in many things he was very old-fashioned, and she had hitherto supposed that speaking frankly of another person’s kind aunt was one of them.

He duly led her into the set, and the dance passed without incident. Though Miss Ogilvie did register thankfully that Lord Lavery was in another set.

At the conclusion of the dance the Admiral led Pansy to a little sofa, and sat down beside her with a sigh. “Well, well,” he said, shaking his head: “dare say, when all is said and done, a hen might suit the boy best, after all.”

Pansy went very red and did not say anything.

“Not but what one cannot tell: Christina, that was his ma, had ‘hen’ writ all over her, but did not give a fig for any of her children. Only interested in them damned dogs of hers. And in stuffin’ herself with sweetmeats. Meself, I wouldn’t have been inspired by her example to seek out another hen, but I have heard it said that a lad who lacks a mother in his youth will look for one, when he decides to marry.”

“That is surely a facile and overly simplistic theory, sir,” returned Pansy grimly. “Human nature, I venture to suggest, cannot be categorised in terms of A plus B.”

“As if we were all algebraic propositions, hey?” said the old sailor with a shrewd look in his bloodshot eye. “No, well, I’d tend to agree. In especial in the case of a fellow with a few brains about him. Though domestic harmony must count for something, and after all, that is what the hen type specialises in, ain’t it?”

Pansy was now too angry to consider her words. “You, of course,” she retorted in a shaking voice, “were thinking of domestic harmony when you chose to marry Portia Fairbrother!”

“You’re out, there,” he said calmly. “Knew exactly what she was like. Knew I’d have to share her, more than like, after a few years, too. I’m not claimin’ to have more brains than me nephews—nor, indeed, than Zeb, their pa: he was a bright lad. But then, I’ve never been particularly capable of self-deception: that made the difference, y’see.” He gave her a mocking look.

Pansy chewed on her lip. “I beg your pardon, Sir Chauncey, I did not mean to be rude.”

“No, well, don’t care if you did,” said the old man, patting her hand. “In some ways, y’know, I’m a bit like Wynn: think that’s partly why Portia agreed to marry me: saw something she could recognise, and had always liked. Added to which,” he said, his eyes now faraway, “she could see I knew a damned sight more about women than them stupid boys that had been dangling after her. Aye...” He gave a gusty sigh. “But,” he said, blinking slightly and patting Pansy’s hand again, “my type would not do for you, me dear. Portia’s always enjoyed playing the little girl: no need to tell me it ain’t a rôle you relish.”

“No,” said Pansy faintly.

“Mind you, all the Winnafrees like their women pretty,” he said, shaking his head again, this time with a very dubious expression on his broad face. “Pretty and feminine, whether or no they prefer ’em with brains.” He eyed Dimity and Mr Winnafree, now whirling in the waltz together. “And Lord knows, I’ve seen it often enough: pretty young thing, all frills and smiles, unfortunate fellow falls for her with a thump, they gets hitched, he never thinks to ask himself what her essential nature might be under the frills—can’t blame him for that, Nature don’t give him the chance: ten years down the track she’s ruling him with a rod of iron, has given up entirely on the frills, covers her hair with damned caps, and ain’t interested in so much as havin’ her hand kissed. Let alone in trying to please him.”

“The fault in such cases,” said Pansy stiffly, “is surely not all on the one side?”

“Never said it was. Wasn’t talking about fault, or apportioning blame. What I’m saying, that is the usual risk a man runs when he marries for the frills and smiles.”

“And the eagerness to please,” said Pansy on a grim note, following his glance, which was now resting on Fliss and Lord Rupert.

“Aye.”

“I have, however, observed that if the frills and the eagerness to please be not there, a man will not marry at all,” said Pansy in a hard voice.

“Oh, exact, me dear, that is how Nature ensnares the poor fellow!” he said cheerfully.

After a moment Pansy said: “You paint a depressing picture of the human lot, Admiral.”

“Dare say I do. Lived a long life, seen a fair amount.”

Pansy’s mouth was very tight and angry, but after a few moments she managed to say: “And the consequence of this neglect of the frills and smiles on the woman’s part, is simple neglect on the man’s, is that it?”

“Well, usually. If he’s got the guts to cut loose from the apron strings at all. Now, I’ve said, haven’t I?” he said as she drew an angry breath: “I’m not saying it’s the woman’s fault, dare say she can’t help herself, neither. What she wants is a quiverful of brats and the management of them and the marital home. Au fond, that type of woman is not interested in men, me dear. Don’t know if you can understand that?”

“Yes, I can,” said Pansy shakily. “I have observed many women to be like that. Certainly Mrs Bridlington whom we knew in Oxford.”

He gave her a sharp look. “Aye, it’s common enough. That, you see, was what I did not want; and what I knew I did not risk endin’ up with, with Portia.”

“Yes, I can understand that.”

Sir Chauncey’s eyes twinkled a little: he could see that she could, indeed, but that it had not hitherto dawned on Miss Ogilvie that he himself might have understood it from the beginning! “Aye, well, the general run of hens, y’see, will take that path in life, as like as not. Well, your Aunt Parker’s a prime case. Decent enough woman, within her lights, but it’s plain as the nose on your face that she bores that fellow to distraction. Don’t bother to tell me he’s too much of a damned Christian to let it show.”

“I—I have to admit, I agree with you,” said Pansy limply.

“Aye.” He paused. “But then, she never had two penn’orth of brain to start with, that’s clear enough.”

“Y— Oh.” Pansy’s nostrils flared angrily. After a moment she managed to say stiffly: “Then perhaps you would care to favour me with your description, Admiral, of the fates of the couples in the case when the woman is not a hen, and does have a few brains?”

“Would have thought you could have worked that out for yourself,” he said airily—sounding, indeed, so horridly like Wynn Fairbrother that Pansy had to swallow. “Well, the case ain’t so common. Usual thing is, she will bury herself in good works, if she be that way inclined. Ever met a Mrs Lestrange in town? One of them charitable Whig ladies: acquaintance of the little Marchioness of Rockingham. Attractive enough woman, but don’t give a damn about her gowns, and less than a damn about Lestrange. Then there’s the sort like that damned Herbert woman. You wouldn’t have met her, me dear: neighbour of ours, never comes up to town. Bruisin’ rider to hounds, breeds the best hunters in England. What good that is to Vic Herbert, when there is never a decent meal in his house, let alone a smile at his board, is beyond me.”

“May a woman not have any interests, then?” said Pansy tightly. “Should it be her lot in life to remain her husband’s pretty toy all her days?”

“Not saying that. Merely, tellin’ you what I have observed.”

“If you are implying that I will develop into a Mrs Lestrange, whom I have never met—”

“There’s the Herbert female as well.”

“Thank you, Admiral, I quite take your point, you do not need to stress it further. If that is what you are implying, then perhaps you had best warn your nephew off?” said Pansy nastily.

“Think I might, actually,” he said on an apologetic note, scratching the fluffy white curls above his ear. “Might advise him to go for the hen type—safer in the long run. Well, better odds that she’d still notice he was alive ten years down the track, not to say still care about pleasing him. Don’t think James could be happy living with a woman who didn’t care about pleasing him no more.” He got up, creaking a bit. “Aye, I might mention it to him. Stubborn lad, mind you, but the instance of the Lestrange female is enough to give any sane man pause.”

He went slowly away, shaking his head, affecting not to notice that Miss Ogilvie was bolt upright, her cheeks an angry scarlet and furious tears sparkling in her eyes.

Subsequently the old man was observed to speak seriously to his older nephew. Lord Lavery was seen apparently protesting, then laughing; and then he was seen being led up to a Miss Kitty Mainwaring, one of the Tarlingtons’ many cousins, fully seventeen years of age, and with the silliest laugh ever to have graced a ballroom—not to say the yellowest curls, the which she was given to shaking violently upon no provocation whatsoever. Miss Kitty, giggling terrifically and shaking the curls tremendously, was then seen to allow his Lordship to lead her onto the floor for the waltz. And the dance after that, too.

Mr Tarlington had very naturally not been unaware that his mamma had been sitting with Henrietta. When her Ladyship rustled away, he was about to approach his cousin—though not at all sure, from the stunned expression on her face, whether this would be the right move—when his father’s elbow connected violently with his side.

“For God’s sake!” he gasped. “Do you wish to edify the neighbours by battering me to death in our own ballroom, sir?”

“Thought you was out of condition,” replied his sire smugly.

Aden glared at Sir Gerald’s bulk. “I am not out of condition, and if it were not that you have the excuse of your age and infirmity—”

“Pooh. Quite a fit man, apart from the damned leg,” he said complacently.

Aden’s jaw dropped. Such had most certainly not been Sir Gerald’s claim within recent memory!

“Come along: I’ll have this next with little Miss Henrietta,” he said complacently, “and then you may have the one after that. Dare say you might take her in to the supper, too.”

“Have you—uh—have you and my mother had words upon this subject, sir?” croaked Aden.

Sir Gerald looked down his nose at him. “Yes, if y’must know, and we are perfectly in accord that it is past time that you was settin’ up your nursery. Got damned tired of waitin’ to see me grandchildren at me knee, y’know. No intention of waiting until your brothers are old enough to father a parcel of brats. Added to which, don’t count. Need an heir.”

“You have several heirs, sir,” replied Aden weakly.

“Don’t hand me that load of nonsense, if you please, Aden,” he said coldly, taking his elbow in a steel-like grip. “Come on, or that damned parson fellow from Merrifield will get his sticky paws on her.”

“Er—oh: Crutchleigh? He’s a very respectable fellow,” said Aden feebly.

“Hand like a warm, damp sponge, no sane girl will want that a-pawin’ her in her marriage bed—but that don’t mean the father won’t look favourably on the damned fellow, he’s a parson like he is himself. And a damned sight-better lookin’ than what you is, Aden. Not to say,” he said awfully, “a good ten years your junior. Dare say the little thing is too young to see he ain’t nothing what might be called a man,” he ended with a sniff.

“Do I conclude you flatter me, sir?” said Aden faintly.

Ignoring this, Sir Gerry steered him up to Henrietta. “Well, two bad pennies, eh, Miss Henrietta?” he said breezily. Henry smiled palely. “Dare say we might creak round the floor, hey? Not in my dotage yet,” he said, releasing Aden’s elbow.

“Y— Um—thank you, Sir Gerald!” gasped Henry, staggering to her feet.

“Aden may have the next. Told him he’s to take you in to supper, too,” said the baronet, leading her firmly into the set.

Henry smiled feebly and was incapable of utterance.

During the dance he passed some very obscure remarks, as they came together in the figures, on the subject of sticky paws and damp sponges. As his own hand was very warm but not unpleasant, and Henry was aware that his son’s was a hard, lean hand, she could not, really, imagine who on earth he meant. Or was he speaking generally? But if so, why?

“Quite a pleasant little hop. Mind you, she don’t dance like that red-haired dasher what was after you—now, was that two year since?” he reported to his son at the conclusion of the measure.

“I’m very relieved to hear it: that is, if you mean the red-headed creature who was throwing herself at Vernon the last Season he spent in London,” replied Aden coolly.

“I don’t mean no such thing! Remember that one very well: one of the damned Brinsley-Pughs!” he replied huffily. “Freckles, bosom like a pair of pimples, must have been mad to think he’d ever look twice at her! No: Felicia B.-D.,” he said, giving Aden a hard look.

“That hair is said by the cognoscenti to be auburn, sir,” replied Aden politely. “If, as I collect you do, you mean Mrs Alf Hemingway.” –At this point Henrietta was heard to gulp: Aden swallowed a smile.

“Right. Not one of the senior branch of the damned B.-D.’s—just as well,” he noted.

“Just as well for whom, sir?” asked Aden politely.

“For poor damned Alf Hemingway, o’ course. –Well, go on! Ask her!” he said on an irritable note.

“May I have the pleasure of this waltz, Miss Parker?” said Aden, bowing very low.

“Thank you,” replied Henry limply.

Smiling, Aden took her hand. “That is, if you can bear to be deprived of her company, Father?” he added sardonically.

“Get on with it!” replied the baronet crossly.

Shrugging slightly, Aden led Henry onto the floor.

“We don’t have to,” she said in a tiny voice.

“Of course we have to, or I’ll never hear the last of it!”

“Y— Um—” Henry tried to smile, and failed.

“Though if the sensation be particularly unpleasant to you, I shall of course brave his wrath,” he said, taking her competently in his arms.

“No, of course it isn’t, don’t be silly,” she said limply.

Aden smiled, just a little. They danced in silence for a few moments.

“Mr Tarlington, I have to ask this, or burst!” said Henry desperately.

Aden’s heart hammered rather hard: he thought she was about to reveal what his mother had said to her. “Yes?”

“Why was he talking about damp hands?” said Henry desperately.

“Eh?” he returned limply.

“Your father: during our dance. He— I do not think I was mishearing. Does he think you have damp hands, or—or do I?”

Aden squeezed the one he was holding in his. “Only pleasantly warmish.”

Henrietta gulped. “Oh.”

He took pity on her. “It was not you. I cannot say how he knows—oh, it must have been when they shook hands this evening—but he has taken the Reverend Mr Crutchleigh’s hand in the greatest aversion. Even going so far as to say,” he said meanly, “that it is not the sort of hand a maiden would wish to have pawing her on the nuptial couch.”

“The sort of— He cannot have said that!” she gulped.

“Of course he could,” drawled Aden. “Surely you have observed that he is one of those persons who is almost completely self-absorbed, to the point where he does not care about, and very largely does not notice, the effect he may have on his interlocutor?”

“Yes,” said Henry faintly. “You are very acute, Mr Tarlington.”

“Sufficiently. But also rather detached, even with regard those closest to me. It is a trait which I have observed to some extent in yourself—and certainly in your Cousin Pansy. It is also a trait which many people find insupportable, or, at least, intensely irritating. I hope you are not one of them?”

“No!” gasped Henry, now thoroughly off-balance.

Aden smiled, but said merely: “I’m glad to hear it.”

They waltzed in silence for a while.

Eventually he murmured: “May I say how improved your waltzing is, Cousin Henrietta?”

“Thank you,” said Henry limply.

“Do you remember that day in the town house? Uh—forget who else was there. Wilf, I think, at any rate. We assisted in your dancing lesson.”

“Yes, I remember,” said Henry faintly.

“You were more interested in Rob Roy than in myself,” he murmured.

“I—I was very young,” faltered Henry.

“Uh-huh. Time marches on, do it not?”

“Yes,” said Henry, very, very faintly.

Aden cleared his throat. “Has Papa been maundering about me turning forty within the foreseeable future?”

“No!” she gasped, turning scarlet. “It was not h— No!”

He bit his lip. “I see. I think I must tell you, though perhaps it is not the time nor the place, that my mother has nothing whatsoever to say in my decisions. In fact, if I were constrained to be crudely explicit, I should point out that since I hold her purse strings, she will eventually—er—give in, on any subject upon which we—”

“No!” gasped Henry in horror. “It was not like— Oh, pray stop! I cannot bear to hear you so bitter!”

Mr Tarlington had stopped. Swallowing hard, he said: “Shall we sit down?”

“Mm,” agreed Henry, blinking.

He led her over to a curtained alcove.

“Um—we can’t go in there,” said Henry feebly.

“Rubbish; get in,” he returned, frowning.

Henry went in without further argument. There was a small sofa in the alcove: she sat down on it without being prompted.

Mr Tarlington sat beside her, looking grim.

“Mr Tarlington,” said Henry bravely, taking a deep breath, “you do not understand your mamma at all.”

He had always been of the opinion that, on the contrary, he understood her only too well. He looked at Henrietta narrowly. “Oh?”

“No. She is a very unhappy and disappointed woman,” said Henry firmly.

Aden’s lean cheeks reddened. “Look, if she has been feeding you a load of nonsense in order to arouse your sympathy—”

“No! I said, you do not understand her at all! Will you just listen!” cried Henry.

A twinkle crept into Aden’s eye. Miss Henrietta was disturbed, but it was hardly the maidenly disturbance of one who has just been warned off a prospective suitor by the suitor’s ma, or his name was not Aden Tarlington. “Very well, I’m just listening,” he said meekly.

Henry took a deep breath. “She told me a lot about her early married life, when Sir Gerald was very keen on growing roses, and something about your next brother, who died.”

“Uh—little Tommy? I don’t remember him,” said Aden feebly.

“He was a little fair boy, and your papa doated on him, and his death soured him,” she said firmly.

Aden blinked.

“Then she was telling me something of their later life, after your grandpapa died and she became Lady Tarlington and had to open up the town house and entertain for your papa.”

“‘Had to’,” echoed Aden faintly.

“Yes. I fail to see,” said Henrietta firmly, “why gentlemen assume that such matters come naturally to those of my sex. They are no more natural than the skills of riding horses or doing mathematics, and must be learned in the same way. Your mamma has had many disappointments in her life, and—and I felt quite privileged that she felt herself able to speak to me of some of them. I am aware that the whole of Society, not to mention all of her own family, has assumed that this engagement of Fliss’s represents a signal triumph for her, but it is not so, and she can see as well as anyone—for although she was not permitted an education she is as intelligent as you or I!” she noted fiercely: Aden blinked again—“that if they are happy enough now, they stand as much chance of remaining so as any average couple, and that marriages between cousins are not wholly desirable!” She glared at him.

“Marriages between—”

“Do not dare to draw any general conclusion from that, for she had no intention of suggesting one!” said Miss Parker fiercely.

“Uh—”

“It was she, not Sir Gerald, who mentioned your age, sir, as you have apparently guessed, and—and it is another disappointment to both of them!” ended Henrietta, now very flushed.

“Uh—ye-es... Good God. You’re not telling me that Mamma indicated she wished to see you providing grandchildren to stand at her knee, are you?”

“She did not say so in so many words, in fact it was Sir Gerald’s knee which was mentioned in that connection, and why someone who claims to your detachment in the matter of close relations cannot see that she is as aware of his character as you are yourself, is beyond me!” Henry rose, still very flushed. “I shall go back, my mamma does not care to see her daughters sitting out like Porky Potter.”

Forthwith she returned to the ballroom, without awarding Mr Tarlington another glance.

Aden laughed weakly. But to say truth, he felt extremely shaken: Mamma had indicated to Henrietta her approval of a match between them? He sat there for some time, contemplating the matter.

Lord Lavery had danced two dances with Miss Kitty Mainwaring. He had danced two with Miss Letty Price-Tarlington, about the same age and just as giggly, though with a simper and a mop of brown curls rather than a silly laugh and a mop of yellow. He had danced a pair with his Aunt Portia. He had danced with Lady Pamela Sotheby, a very elegant married lady of possibly around his own age, who was one of Lady Tarlington’s Gratton-Gordon connexions: from the senior branch, and in fact a daughter of the present Marquess of Wade. Then he had spent some considerable time sitting out with Lady Pamela, laughing and talking. At the conclusion of this pleasant interlude Lady Pamela was seen leading him up to her little sister, Lady Alicia Gratton-Gordon. Scarce seventeen and by rights did not ought to be present in her connection’s ballroom at all. She had the riotous black curls which characterized her brother, that dashing hussar Captain Lord Vyvyan Gratton-Gordon, but instead of being tall like her brother and sister, was shortish and slim.

“Sylph-like, is she not?” said a mocking voice in Pansy’s ear at this juncture.

“I am sure,” replied Pansy grimly.

Mr Tarlington laughed. “Though Sir Chauncey has just relieved all our minds by informing us that she ain’t skinny!”

Palsy could see that for herself. “Quite.”

“Out of course, I scarcely know Lavery, but—”

“Then why did you invite him?” she retorted angrily.

“I did not, Cousin Pansy, this ain’t my house,” he drawled.

Pansy’s lips tightened.

“As I was saying, I don’t know him, but if you were to smile on him, I doubt he would look twice at those dim little snippets of girls. Or at Lady P., either,” he added drily.

“On the contrary, one collects that his uncle is encouraging him to look at them. If it be any of your business.”

Mr Tarlington came up very close and said in her ear: “Pansy, don’t let that stubborn nature of yours lead you into ruining your whole life. If he’s the man who could make you happy, take him, for God’s sake.”

Pansy’s hands clenched into fists. “Go away,” she said hoarsely. Aden could see that the big brown eyes had filled with tears. He shook his head slightly, but said no more, and did go away.

Pansy sat back in her chair fighting off tears, no longer capable of telling herself that it was all frivolous nonsense and social nothings, or that dancing with a pleasant gentleman mattered not a whit in comparison with such serious matters as the poverty and disenfranchisement of the working man, or the education of women.

... “I hate to think what plot you have dreamed up, my darling,” said Portia lightly to her spouse as he appeared at her side just as the supper dance struck up, “and pray do not tell me just at present, l doubt my nerves could stand it; but I will just say this, reluctant though I am to admit it: judging by the look on Pansy’s face, it almost looks as if it may be working.”

“Keep your fingers crossed, then!” he said with his rumbling laugh.

“I shall endeavour to do so, though it will not be easy, while I eat my supper. Shall we dance this one, Chauncey?”

“Why not?” Amiably the Admiral led his little wife onto the floor.

Henrietta, meanwhile, had had plenty of time to wonder if Cousin Aden would after all dance the supper dance with her as his father had commanded him. He had not come near her since she had left him in the alcove. He had been dancing, however—but only with quizzy cousins or aunts or other older ladies, so presumably he was doing his duty as the son of the house. He danced one with his mother, and Henrietta, politely refusing a very young Mainwaring’s invitation, sat against the wall and watched in fear and trembling. But they appeared to exchange almost no conversation. It was a waltz, and their steps fitted perfectly: they were the most graceful couple on the floor. At the conclusion of the dance Aden bowed very low. Henry, watching dubiously, did not think it was a mocking bow. Lady Tarlington permitted him to kiss her hand, but her face remained as discontented as ever, so Henry did not know what conclusion to draw.

When the supper dance struck up she was sitting with the three Claveringham sisters and Alfreda. Theo came up and immediately solicited Lady May’s hand. Lady Hubbel would most certainly not have approved of the way in which she hopped up, smiling into his eyes, and allowed herself to be led onto the floor.

“We have decided,” murmured Sarah, looking at Henry’s face. “that we do not care what Mamma may say—have we not, Jane?”

“I see!” gasped Henry, jumping, and smiling weakly at them.

“They may have to wait until May is of age—but the wait will not do her any harm,” said Lady Jane placidly.

Sarah nodded. “Of course Mamma will see to it that she does not get a penny of Claveringham money, but if Grandmamma is still alive she may rectify that. Not because she particularly cares for May,” she noted drily.

Henry bit her lip but nodded.

“And we know,” added Sarah more gently, smiling at Alfreda, “that your dear papa may not entirely approve: but in the end I think he will see that the prejudice is an unreasonable one, and will permit two blameless young people to be happy.”

Henry nodded hard, swallowing and blinking.

“Broughamwood very much likes Mr Parker,” contributed Lady Jane.

“Your brother? I was not even aware that they had met,” said Henry limply.

“Oh, yes: he is very interested in the Oxford school project,” replied Jane serenely.

Theo’s and May’s future seemed to be assured, then—certainly once Viscount Broughamwood became the Earl of Hubbel, if not sooner.

“May has actually admitted to us that it will do her so much good, to learn to possess her soul in patience!” added Jane with her gentle laugh.

Henry smiled, but a trifle uneasily: out of the corner of her eye she could see Sir Gerald approaching, leaning heavily on his son’s arm.

“Ah!” announced the baronet, beaming down at them, wheezing slightly. “Pretty clutch of young heifers, hey?” he said to Aden.

“At least he has not likened you to Yorkshire White swine, be thankful for small mercies,” said Aden to the blushing young matrons. “And I question whether Lady Jane may be strictly considered to be a heifer, sir: for she has produced her first offspring.”

“I think that is quite enough, Cousin Aden!” said Alfreda with a smothered laugh. “We heifers, you know, are not dancing this evening, but perhaps you would care to lead Henry out for this one?”

“Of course he would, foolish fellow. Get on with it, Aden,” said his father. “Hop up, me dear, and dance with the fellow: then I may take your seat,” he said to Henry.

This left Henry very little option, of course. She got up hurriedly and Sir Gerry sank down next to Alfreda with a sigh, taking her hand as he did so and squeezing it in an apparently absent-minded way.

“Shall we?” said Mr Tarlington, bowing.

“Thank you,” replied Henry limply, feeling the eyes of all three ladies, not to say those of Sir Gerry, positively boring into her.

“My father informs me,” said Aden, after they had circled the floor twice in absolute silence, “that I shall have something particular to say to you tomorrow, Miss Henrietta.”

“You are being very silly,” said Henry faintly.

“No, but he is! Thank God he has given up hunting: you never saw anyone cram their fences like Pa was used to.”

“I think you are fond of him after all,” discovered Henry, looking up into his face.

“Er—so far as one may be, I think. Given the family history.”

“Yes,” said Henry, squeezing his hand.

To her astonishment she then saw Cousin Aden go bright red and his hard grey eyes fill with tears. “After the wedding?” he croaked

“What?” replied Henry in confusion.

Aden licked his lips. “I’ll speak to you after the damned wedding. Let’s get all the fuss and the damned guests out of our hair first, mm?”

“Yes,” said Henrietta in a tiny, tiny voice.

Aden said nothing more: just held her to him far more closely than was seemly in his mother’s ballroom, and whirled her into the dance.

… “That’s all right, then,” concluded Sir Gerald simply.

As he was still holding Alfreda’s hand, she squeezed it warmly and replied, smiling: “Why, yes, I think it is, sir!”

He winked. “You can stop worrying: I’ll leave the rest to him—keep me big mouth shut, hey?”

Regrettably, at this artless speech those three respectable young matrons, Lady Harpingdon, Lady Jane Carey and Lady Sarah Quayle-Sturt, all collapsed in giggles, nodding helplessly.

Sir Gerry just grinned, very pleased with himself.

Pansy was just making up her mind, having belatedly realised it must be the supper dance, that even if it would make her remarked and upset her aunt, she would go upstairs to bed, when she was stunned into immobility to see herself approached by both Winnafree twins, plus Mr Winnafree’s fiancée.

“There you are, Pansy!” cried Dimity gaily. “We are in need of your aid: you must absolutely promise to lend it!”

“We beseech you, Miss Ogilvie!” said John Winnafree with his pleasant smile.

“Y— Um—if I can,” croaked Pansy, not looking at Lord Lavery.

“We have just learned,” explained Dimity, “that the Tarlingtons are to close up Guillyford Place not three days after the wedding: Lady T. has a long-standing engagement and Sir Gerald has been persuaded by an old friend to go somewhere truly odd for some new waters.”

“Yorkshire?” suggested Lord Lavery solemnly.

“I am sure you may be right, James, my dear!” replied Dimity gaily, opening her eyes very wide at him, and both sounding and looking exactly like his Aunt Portia. “Or was it Cumberland?”

“It could have been Wales,” he said solemnly.

Giggling, Dimity said to Pansy: “Well, you know what he is like, dear Pansy: his discourse is at best rambling! But he will most definitely not be here, and Mr Tarlington has promised to escort his mamma, and though he will come back, the house will be utterly closed in the meantime!”

“Er—yes?” said Pansy limply.

“But Pansy! Dr Fairbrother’s and Miss Blake’s wedding!” she cried.

“Has he told you? It is in less than three weeks, Miss Ogilvie,” said Lord Lavery solemnly.

“Ye-es... Oh, help, do you want to stay on for it, Dimity?”

Dimity nodded hard. “I was absolutely sure that we would! I mean, I never questioned it for a moment! After all, Fliss is terribly fond of him and Lord Rupert has got her two parrots from him!”

“Ye-es... But Fliss and Lord Rupert will be—well, I am not sure, but they will either still be on their honeymoon, or just settling into their own house. And—and Dr Fairbrother and Miss Blake did not—um—consult anybody’s convenience, you know, when they decided on the date, so—so if people cannot make it in time, they—they must blame themselves,” said Pansy, ending on a very limp note indeed. Why was the horrid man smiling at her, so? When he had ignored her for the entire ball!

“That is very true, Miss Ogilvie,” said John seriously, “but Dimity has quite set her heart on attending the wedding.”

“Y—but Dimity, you scarce know Dr Fairbrother,” said Pansy feebly.

“I know him a little, and of course I know Miss Blake very well, and I missed out on everything the other time, and I am absolutely determined not to be the only one to miss out on the wedding!”

“Y— Um—”

“And dear Lady Jane has said that of course you and I and Henry must stay with her, but as they will have Lady Sarah and Mr Quayle-Sturt as well, their little house will be rather full.”

“Actually, I am to stay at the school,” said Pansy limply. “You may share a room with Henry, in that case, Dimity, so that seems quite—quite satisfactory. Um, help, is my Aunt Parker raising objections?”

“No, no! Well, she said that I am to be very, very good and that Lady Jane and Commander Carey will look after me splendidly. And naturally there is no reason why I should not be very good!” said Dimity with a radiant face.

Absurdly, Pansy suddenly felt she might burst into tears. Her throat constricted. “No,” she agreed hoarsely.

“And, um, well, the arrangements afterwards might have been a trifle difficult, but dear Sir Chauncey and Lady Winnafree have said that I must come to them, and Aunt and Uncle Parker will meet us there in May. And we shall go on to Lavery Hall,” Dimity ended, blushing very much.

“For the wedding,” said Lord Lavery, smiling.

“Yes,” agreed Pansy hoarsely. “Of course.”

“It is a pity that Lady Harpingdon will not be able to attend,” he said, still smiling, “but with the baby due in June, it would be ill-advised. But Mrs Parker will be able to go straight down to Harpingdon Manor after the wedding, so at least that will cut down on the amount of travelling she will have.”

“Yes, and if it is a girl, Alfreda has promised that Dimity will be one of its names as a compensation!” beamed Dimity.

“Er—yes. Very nice. Dimity, I cannot see there is any problem.”

“But Pansy: the twins!” she cried.

“Yes, indeed: we are the fly in the ointment!” said John Winnafree gaily, taking her hand.

Pansy went very red and did not look at his brother. “But— Um—”

“You see, the thing is,” said Dimity earnestly, “they do not wish to batten off dear Sir Chauncey’s charity by staying with him and Lady Winnafree in an hotel at Brighton.”

“Uncle Chauncey is all that is generous. But he always puts up at the best hotels, and really, if there is an alternative— Well, the thing is, Miss Pansy, we had hoped that in this instance there would be an alternative,” said Mr Winnafree.

“What?” replied Pansy stupidly.

“Could they not stay in your dear little cottage, Pansy?” said Dimity, opening her eyes very wide. “Just for three weeks—less, really.”

Pansy’s jaw sagged. “Um—but there is Horatio!” she gulped.

“We like cats,” said James meekly.

Pansy looked suspiciously at him. Lord Lavery’s face was expressionless. She looked at his twin.

“Yes, we do,” John confirmed calmly.

“Though it is true,” admitted Dimity, pinkening, “that Horatio Nelson Cat does not care for gentlemen.”

“Um—there is Ratia Bellinger, too,” said Pansy, gnawing on her lip.

“Oh, but she will have to get used to them anyway!” cried Dimity.

There was an awful silence.

“What she means is, that Ratia Bellinger cannot live her whole life as if the opposite gender did not exist,” said James smoothly.

“Yes, exactly!” gasped Dimity desperately.

Valiantly Pansy attempted to overlook the fact that both Miss Dimity Parker and her fiancé were now a glowing puce shade. And that the former was very obviously lying in her teeth. “I suppose it would be all right,” she croaked. “Though it is not very comfortable for gentlemen.”

“Pansy, my dear, it cannot be worse than those awful lodgings they had in London,” said Dimity earnestly, recovering herself.

“Er—can it not? Surely you were not allowed to visit there, though?”

“No, of course not, but Lady Winnafree has told me all about them. So they may?”

“Yes, of course,” said Pansy limply. “But—but there is no proper stove, sirs.”

“I have told them all about that, and they will cook on the spit, just as you and Delphie did!” said Dimity, now positively radiant. “Oh, thank you so much, dear Pansy!” She embraced her heartily. Pansy staggered slightly, and smiled weakly as Mr Winnafree then thanked her fervently.

“Oh, my goodness, we have missed the supper dance!” Dimity then discovered brightly as it ended. “Never mind, there will be other dances! –Pansy, you must sit with us. Come along, John.” She linked her arm in his and led him off forthwith.

“That was an order, not a request, Miss Ogilvie,” said Lord Lavery, bowing and offering her his arm. “You must give John the chance to express his gratitude properly, you know.”

“He just has. And pray tell me,” said Pansy, taking a deep breath, “why it is that a gentleman of your position cannot afford to put himself and his twin up at an hotel for a few weeks?”

“Well, the thing is, John dislikes living off my charity as much as he does off Uncle Chauncey’s,” he said apologetically.

Pansy went bright red and gasped: “I’m so sorry! I do beg your pardon!”

“Not at all. I did not say anything, you know, because this was all Dimity’s scheme and I knew John wanted it very much. But if you don’t want me in your cottage, just say so, and I will put up in Brighton.”

“Don’t be silly, of course you must use the cottage,” said Pansy stiffly, avoiding his eye.

“Thank you, I should love to.” He smiled at her. “John really will wish to express his appreciation, so shall we go in to supper?”

“Thank you, Lord Lavery,” said Pansy limply, taking his arm.

In the supper room Dimity and John were discovered already ensconced at a table with Admiral Sir Chauncey, Lady Winnafree and Dr Fairbrother. Pansy could not help feeling that this was not a coincidence and that the way in which all of these persons and her irritating escort then proceeded to treat her as one who was of right included in their party had nothing of the coincidental about it, either.

She was both hoping and dreading that after the supper Lord Lavery might solicit her to dance. She knew she ought to refuse him, if he did, but doubted she would have the courage. And if he did not, it would just prove that he was a heartless flirt and not a man of sense and—and did not care, in spite of anything he might have said to the contrary! And a hen would be welcome to him!

But instead, Dimity took her arm, and said firmly: “Now, let us go and chat to Lady Jane and the Commander about our plans! Come along, John!” Mr Winnafree, smiling, took her free arm. “Take Pansy’s other arm, James,” added Dimity carelessly.