32

All’s Well That Ends Well

The happy couple had been waved off in a shower of tears (largely from Mrs Parker, Dimity, and assorted girl cousins of the bride’s), and the majority of Guillyford Place’s house guests had taken their leave in a flurry of carriages, outriders, postboys, grooms, contradictory instructions from Sir Gerry, and so forth. And there were only the Parkers, the Harpingdons and the Winnafree party left.

At almost the last minute Mrs Parker suddenly bethought her that as Guillyford Bay was almost on their direct route they might drop the girls off after all: but Theo and Mr Parker pointing out firmly that it was not on their direct route at all but on the contrary in the opposite direction, she was got into the coach. Bethinking her at the very last minute that, since Harpingdon Manor was after all almost on their direct route there was no reason why they should not join up with Alfreda’s and Christian’s party and travel togeth— But Mr Parker put the window up firmly and Theo, who was riding beside the coach as far as the turnoff for the London road, ordered the postboys to set off.

The Harpingdons were not long after them: Mr Tarlington wringing Harpy’s hand and advising him drily to thank his lucky stars, and not even the Narrowmine twins having to ask why.

Which left Sir Chauncey’s party and the young ladies who were to put up at Buena Vista or Merrifield School.

“James will take you, Pansy,” said Portia calmly, as Pansy appeared in the downstairs salon with her pelisse and bonnet on.

“One might say, otherwise there will be too much of a squeaze in the coach,” said James, just as Dimity was opening her mouth to say that very thing, “but as one is aware that you dislike prevarication of any kind, Miss Ogilvie, one will not. I should very much like to escort you. May I?”

Ignoring the fact that Dimity was smothering a giggling fit with her brand-new blue kid gloves, Pansy said feebly: “Thank you. But—um—what in?”

Ignoring the fact that Dimity had given an agonized squeak and was putting the gloves through further torture, James replied solemnly: “Tarlington has lent me one of the Place’s curricles. He assures me that I will get considerable use out of it at Elm-Tree Cottage, and that there is a boy who will come and help Ratia Bellinger to look after the horses.”

“Not a team?” gasped Pansy.

“No, a pair only.”

“But Lord Lavery, there is only a shed, it is not nearly big enough for two horses.”

“In that case I shall see what can be arranged with the landlord of the local inn.”

“Y— But then you will have to walk all the way between there and the cottage.”

“That is preferable to having no transport at all, I feel. Will you be warm enough in that pelisse?”

Pansy had of course assumed she would be travelling in the usual swaddling comfort of Sir Chauncey’s coach. She looked down at herself blankly. “Oh.”

“My dear, you must borrow this fur cloak of mine,” said Portia, bustling forward with it. “Now, we are quite ready, I think, and we have said our good-byes to Lady Tarlington, so we shall be off. Take very good care of Pansy, James, my dear, and mind her when she tells you which turn to take.”

Smiling, James kissed his aunt’s cheek. “Of course! We shall see you very soon. We shall meet at Philippi,” he added solemnly to his twin.

“I promise to spur the famous Ratia Bellinger into having hot soup ready on the hob for you,” replied John with a grin.

“Excellent.” Lord Lavery offered Pansy his arm. Limply she took it, and they exited in Sir Chauncey’s and Portia’s wake, followed by Mr Winnafree and Dimity with Mr Tarlington, who had been a silent but very possibly not unappreciative spectator of the previous scene.

“But where is Henry?” said Pansy as they reached the sweep.

“She muttered something about hat-boxes and rushed out,” replied Mr Tarlington.

“Oh! Good Heavens, yes! The hats!” she cried distractedly.

“It’s all right!” gasped Henry, appearing at the top of the steps with a hat-box in each hand. “Here they are!”

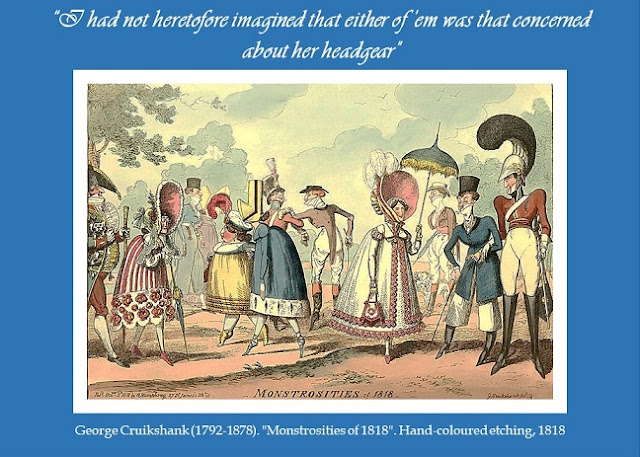

“I own, I had not heretofore imagined that either of ’em was that concerned about her headgear,” said Mr Tarlington to Lord Lavery as Pansy abruptly released his arm to rush over to her cousin.

“Town bronze: must have been the trip abroad, Tarlington,” he replied solemnly. “At the least, in Miss Ogilvie’s case. Though I gather that Miss Parker received a considerable amount of additional bronzing during the Little Season.”

At this point Dimity collapsed in giggles, so the two wits desisted, and merely grinned at each other.

“You are being silly!” panted Henry, coming up to them with a hat-box. “Here,” she said to his Lordship.

Looking somewhat stunned, Lord Lavery took it.

“That one is for Mlle La Plante, from Dimity and me,” said Henry earnestly. “Pray do not let Pansy get them mixed up.”

“I shall not get them mixed up, this is the one for Letitia,” said Pansy firmly, coming up with the other hat-box.

“They are for the wedding,” Dimity explained to her almost-brother-in-law. “For the schoolmistresses.”

“I see,” replied James very weakly indeed.

“Henry and I chose them in London, but of course we consulted with Pansy by letter,” explained Dimity. “They were rather expensive, but then, one does not attend one’s headmistress’s wedding every day of the week! Pansy insisted on paying for Miss Worrington’s: and naturally I was only too willing to bear the total cost of the other, for Henry has very little pin-money, but she would not—”

“Dimity, my dear, you may tell us the whole later,” said Mr Winnafree firmly, seeing that his cousin-to-be’s cheeks had turned puce. “In you pop, my dear: the wind is chilly.”

The Winnafree party was duly got into Sir Chauncey’s coach, and Pansy and the two large hat-boxes were got up into the curricle next Lord Lavery. Curricles not being designed for the conveyance of large hat-boxes, there was some confusion over their exact disposition, but Pansy solved this capably by putting one by their feet, where it discommoded the both of them to what the driver, at least, felt to be a significant degree, and by taking the other upon her knee. What with the hat-box and the carriage-rug, not to mention the fur cloak belonging to Lady Winnafree, not very much of Miss Ogilvie was visible.

To the accompaniment of waves and smiles from Dimity, at the window of the coach, and a forced smile from Miss Ogilvie, the procession set off.

“Whew!” said Mr Tarlington to his beloved with a grin. “That’s the lot of ’em, then!”

Henry smiled weakly.

“Never thought we’d get rid of the Mainwarings within the se’en-night,” he noted.

“Your father’s telling them to push their barrows could not but assist the process of departure,” replied Henry primly.

“True! Run and get into your pelisse. –Wait: have you a fur cloak?”

“No!” gasped Henry. “I have not a fur anything, Cousin Aden,” she added, recovering herself very slightly.

“I’ll borrow one of Mamma’s for you, then. Off you go.”

Smiling weakly, Henry headed for the staircase.

Mr Tarlington, grinning, lounged off to the stables. Where he immediately inspected every axle, spring and joint of his curricle. Not altogether to the surprise of the faithful Tomkins.

“Major, sir, I’ve been over it meself with a fine-tooth comb, it’s as sound as a bell. The only thing what might cause a h’accident with Missy up is if you was to take your eyes orf the road.”

“What?” said his master dangerously, straightening from a last inspection of the wheels.

“Which out of course you won’t, if you does know the Guillyford road like the back of yer ’and.”

Mr Tarlington gave him a hard look but said merely: “I shan’t need you.”

“Right you are, then, sir. Oh: was you h’intending to meet up with Mr Rowbotham on the twenny-third, or not, sir?”

Mr Tarlington’s jaw dropped.

Tomkins looked vindicated. “Thought you might of forgotten—well, what with Miss Fliss’s wedding.”

“Did you, indeed? Uh—what is the date?” he added on a weak note.

“It’s the eighteenth, Major, sir, and seeing as ’ow Mr R., ’e said Bath—” He paused artistically.

“Bath? What is God’s name is Wilf doin’ in Bath in March?” muttered Mr Tarlington.

“Visiting a h’aunt, I believe, sir,” said Tomkins at his most stolid.

“Eh? Oh—yes. Old Miss Catherine Rowbotham. Expectations. Uh—damnation.” he muttered.

“I could send a groom with a message, sir. Acos if you ’as to escort ’er Ladyship to Blenheim, and then get back ’ere in time for the learned gent’s wedding—” He shook his head.

“Ye-es... Damnation.”

“Tell you what, Major, sir, we could tell Mr R. to get on down ’ere: then ’e could join up with us and go to the wedding and everything!” offered Tomkins, beaming.

“Er...” Mr Tarlington’s personal groom seemed to have arranged Mr Rowbotham’s social calendar for him. Mr Tarlington shrugged a little. “Why not? You’d better take him a note yourself, Tomkins. Uh—come into the house, will you, I’ll write it immediately and you can get off to Bath straight away.”

Possibly, though this was not apparent from his manner, this had been Tomkins’s plan all along. “Right you are, Major, sir.”

He accompanied him into the house and waited respectfully enough while his master scrawled a note. However, the impartial onlooker might have said the effect to have been spoiled somewhat by his remarking, as he put it carefully inside his coat: “Dessay we could wet our whistles to it, sir, afore I goes.”

Mr Tarlington opened his mouth. He shut it again. Then, with tremendous restraint, he said: “Why not?”

Two brandies were duly poured. Mr Tarlington raised his glass, his face expressionless. “Go on.”

“Long life and ’appiness to the both of yer, Major, sir,” said Tomkins brazenly.

“Thank you,” returned Mr Tarlington on a weak note, as his groom drained his glass. “Er—I’ll drink to that.” He sipped brandy.

“That’s right, Major, sir, get it down yer: nothing like a sip of Dutch courage when a man’s about to pop the qu—”

“Get out,” said his master evilly.

Grinning brazenly, and touching his forelock insouciantly, Tomkins got.

“Godfather!” said Mr Tarlington madly, sinking into a chair. On second thoughts, however, he finished his brandy.

James and Pansy drove in silence for some time. Eventually, however, Pansy was forced to say, as a fork hove in sight: “It is left for Merrifield, sir.”

Sir Chauncey’s coach had been glimpsed, well ahead of them by this time, taking the right-hand road. James replied cautiously: “Oh?”

“Yes. The road to the right leads only to Guillyford Bay and the sea.”

“Do I have to come all the way back to get to Guillyford Bay from Merrifield, then?”

Pansy went very red. “No, but I am afraid it is quite a drive. I’m so sorry: I didn’t realise you did not know.”

“I came from Brighton, before,” said James feebly.

“Did you?” replied Pansy blankly.

“When I dropped off a monkey!” he explained with a smothered laugh.

“Oh, great Heavens, that was you?”

“Mm.”

“This is dreadful: the schoolmistresses will be utterly overset when they realise who you are!”

“I do not think so.’

“They will!” she cried. “They were persuaded it was a courier!”

“Yes, I know, Pansy,” he said soothingly, “but I spoke only to an elderly maid who opened the door to me, and to Miss Blake herself. Then I was allowed to go into the kitchen, where the maid—oh, and the cook in person, of course!—where they regaled me on beef and horseradish sandwiches, with apologies for the beverage’s being only tea.”

“Thank Heavens for that,” said Pansy, sagging.

“Mm. Do I conclude the maid will take it in her stride?”

“Pointer is a very sensible woman.”

James’s lips twitched. “I see. Not impressible by titles, is that it?”

Pansy took a deep breath. “No, she is not. She will, however, consider you to have acted very foolishly and heedlessly.”

“Any sensible woman might,” agreed James ruefully.

Pansy was silent.

“Left, then,” he said, taking the left-hand fork.

“Yes. –Oh: I’m sorry, I was explaining,” said Pansy lamely. “It is a little quicker from Merrifield to Guillyford Bay if one keeps close to the coast. That road joins up with the Guillyford Place road just before the Bay. I am afraid there is no short-cut to Buena Vista, it skirts the Point,” she added apologetically.

“Oh, that’s quite all right, I shall go straight to Elm-Tree Cottage in any case, for if John says there will be hot soup, hot soup there will be!”

Pansy was trying to envisage Ratia Bellinger (a) coping sensibly with the advent of a gentleman and (b) taking her orders from the meek-mannered Mr Winnafree. She smiled weakly and said nothing.

After quite some time James admitted: “I cannot help thinking of that damned drive we took in Corsica.”

Pansy had been thinking of their drive down the Appian Way. She jumped. “Corsica?” she croaked. “That—that was a very hot day.”

“Mm. Hellish. I spent the entire drive wishing I could work up the courage to tell you the whole and wishing I had never embarked on the damned masquerade and that you would look on me as a man and not as irritating James, the courier.” James broke off, gnawing on his lip. “At the time,” he said with difficulty, “I did not imagine I could be more unhappy.”

“You seemed quite as usual to me,” said Pansy faintly. “Quite—quite as flippant.”

“I suppose I was, yes,” he said sourly.

“I—I quite enjoyed myself,” said Pansy timidly.

“Even though we near came to blows?”

“I—I don’t remember that. It was very hot,” repeated Pansy with a sigh.

“Miss Ogilvie, are you cold?” demanded James abruptly.

“No!” she gasped. “I am so muffled up, I am really very warm. There is quite a brisk breeze, though: are you warm enough, sir?”

“What? Oh. Yes, thank you. I rarely notice the weather.”

They drove on, the silence lengthening.

Eventually Pansy said on a desperate note: “Actually, I was thinking of that other drive: down the Via Appia. Was that not a perfect day?”

“Yes,” said James in a choked voice, pulling the Place pair to a halt.

“What is it?” faltered Pansy, as he fumbled in the pocket of his greatcoat with a rending sniff.

“Miss Ogilvie,” said James, blowing his nose hard, “I thought I could go through with this, but I damned well can’t. Did Uncle Chauncey blather on at you about hens? Mm,” he said as nodded. “Well, he gave me orders to make you jealous by pretending to be interested in hens, and— But I can’t,” he said, blowing his nose again. “Dammit,” he muttered.

Pansy’s hands trembled slightly on the hat-box. She clutched it very tightly and was incapable of speech.

“I don’t think,” said James in a shaking voice, “that I have ever been so miserable in my life. I know you have every right to be angry with me and—and there is no reason why you should forgive me, but—please,” he ended limply.

Pansy looked up at him timidly. James looked back at her, blinking slightly, the normally sparkling sapphire eyes very wet. She swallowed hard. “It’s all right. I forgive you. And I’m sorry I was so horrid to you,” she said in a low voice.

“Really?” he replied, his voice shaking.

“Yes. We are all of us human and fallible, and—and weak. I—I judged you too harshly.”

“Then—um—marry me,” said James lamely.

“Are you sure?” said Pansy in a low voice.

“Of course I’m sure!” he said in amazement, staring at her.

“It’s just that I am not the sort of person who—who thinks of themselves as marrying as a matter of course,” explained Pansy gruffly, blushing.

“No. I will try to spare you the boring bits as much as possible.”

“I wasn’t thinking it would be boring,” she said, staring at him in her turn.

“Er—no?” said James weakly.

“No, of course not! I meant that I—I don’t think I’ll be very good at—at all those things that hostesses have to do.”

“Is that all? Life at Lavery Hall is very informal, you need not worry. I suppose I haven’t told you a thing about it, have I? Well, it’s an old house, near the sea. You will certainly be able to have your little boat. We have lots of horses and dogs, and though my younger sister does have a cat, I am quite sure it will resign the roost to Horatio without a murmur. Um—what else? We do not dress for dinner, unless we are entertaining formally, the which we do very, very rarely!” he said with a smile.

“I didn’t imagine it like that at all,” said Pansy dazedly.

“Then I was a great idiot not to tell you of it before. It is not in the least like Guillyford Place, I promise you. And it will not be until we are a very old married couple and our eldest daughter is old enough to be married off that we shall have to have a frightful affair like the one we have just endured!”

Pansy gave a little choke of laughter. “Wasn’t it terrible?”

“Oh, indeed! But a classic of its kind,” said James, his eyes sparkling.

“Mm!” she squeaked, nodding.

He put his free hand on top of hers, where it was clutching the hat-box. “So you will, Pansy?”

“Yes,” said Pansy in a tiny voice. “If you’re very sure?”

“I am absolutely sure!” said James gaily.

He then discovered the near-impossibility of kissing a young lady who is hugging a large hat-box on top of a fur rug and is to boot swathed in a heavy fur cloak. But somehow he seemed to manage it.

“Oh!” gasped Pansy, very flushed.

“I trust that came up to the expectations raised by such as the Comte de la Marre, M. Lamartine, and assorted conti and baroni?”

“Yes. I—I feel very odd, James!” owned Miss Ogilvie.

James Winnafree gave a shaken laugh, and replied: “Thank God for that!”

If Mr Tarlington considered himself to have undergone considerable rigours at the hands of the faithful Tomkins, Henrietta, meanwhile, was undergoing a not dissimilar experience.

On reaching her room she found the Guillyford Place housekeeper herself in attendance. If there was anything at all Miss Parker required? And Mr Tarlington had sent a message she was to have one of her Ladyship’s fur cloaks: her maid would be along directly with a selection. And if she might be permitted to say so, Miss Parker, the chinchilla would suit a lady of her looks. Or the black sealskin?

There then arrived, in the charge of a smiling Needham, three fur cloaks from which to choose, each with a matching muff—all of gigantic proportions. No, no, of course her Ladyship would not require them, and if she might make so bold, Miss Parker— Limply Henry let Lady Tarlington’s own maid help her into her best pelisse and bonnet, arrange her curls more becomingly under the bonnet, tie the ribbons more becomingly, and choose a fur for her.

By the time she tottered downstairs she was afraid she must have kept Mr Tarlington waiting, but he was just shrugging himself into his greatcoat in the hall. Henry was at first surprised, and then not surprised, to see that the man assisting him into it was not one of the footmen, but Mr Tarlington’s own valet.

“Thank you,” he said with a sigh as the man smoothed the capes over his shoulders.

“Not at all, sir. Good day, Miss Parker. May I wish you a very pleasant journey?” he said, bowing very low.

“Thank you,” said Henry feebly.

“That’ll do, thanks,” said his master heavily.

“Thank you, sir. I have taken the liberty of telling them to put an extra fur rug in the curricle for Miss Parker, sir,” he said, bowing again.

“Very good,” said Mr Tarlington, sounding as if he was saying it through his teeth. “Thank you, Harker,” he added grimly to his papa’s butler, who was bowing very low and handing him his gloves. “I’ll be home—uh…” He looked at the clock. “Oh. Well. expect me back this afternoon.”

“Mr Tarlington, the road is not very good, I think you would be wiser to—to aim at returning by the dinner hour,” said Henry, inexplicably going very red by the time she had finished this speech.

“Very wise, if I may say so, Miss Parker,” said the Guillyford Place butler, bowing, and positively smiling at her. “A prudent man would not spring his horses on that road.”

“Look, that’ll do!” said Mr Tarlington heatedly. “Take yourself off. And take all these damned footmen with you, what the Devil are they all doin’ in the front hall?” he added, glaring round him.

“Certainly, Mr Tarlington. –Timothy, you may give Mr Tarlington his hat.” The butler nodded dismissively and the other footmen vanished like the dew. Timothy, beaming, handed Mr Tarlington his hat rather as if it were the orb and sceptre and Mr Tarlington the chief actor in a coronation.

“Thank you. Come along, Miss Parker, the curricle is outside.”

“I was just giving Timothy Bellinger a shilling: he has looked after me so kindly all the time I have been here,” said Henry, smiling at him.

“Then possibly that explains, though it does not necessarily justify, the presence of at least one of Papa’s footmen in the front hall,” said Mr Tarlington, looking hard at the butler.

“Possibly it does, Mr Tarlington,” he agreed smoothly.

Mr Tarlington took his distant cousin’s elbow in a grip of steel. “You will not give Harkness a shilling.”

“I should not dream of insulting him by offering it!” replied Henry crossly. “Thank you so much, Harkness.”

“What in God’s name has he done to make your stay pleasant?” wondered Mr Tarlington to the ceiling.

“Everything: I think you do not understand how dreadful a stay in a great country house can be to those not very accustomed to the exercise,” said Henry, nobly restraining a start as the butler bowed very low to her.

Mr Tarlington sighed heavily. “Ready? Said goodbye to the housekeeper?”

“Yes: she has been very kind, and so helpful with the arrangements for the children,” replied Henry sunnily.

Rolling his eyes, Mr Tarlington led her forcibly out to the curricle.

“Oh: where is Tomkins?” cried Henry in dismay.

“Not here. Get in, before I strangle you and the entire Guillyford Place staff and run barking mad!” said Mr Tarlington very loudly.

Henry mounted into the curricle but said as Mr Tarlington seated himself beside her and took the reins: “But I wished to say good-bye to Tomkins.”

“I have every hope that you will see Tomkins on a daily basis for the rest of your life, and so, may I add, has he,” replied the driven Mr Tarlington. “Let ’em GO!” he shouted. The groom sprang back, the horses sprang forward, and Henry grasped the side of the curricle with a gasp.

Strangely, the high iron gates of Guillyford Place, as the curricle approached them at a spanking pace, were not closed as was customary, but held wide by two beaming men.

“Godfather!” said Mr Tarlington through his teeth.

Regrettably, at this Henrietta, though waving valiantly to the two beaming gate-holders, collapsed in helpless giggles.

Mr Tarlington managed to drive on for a couple of hundred yards: in fact he managed to get round the nearest bend and out of sight of the Place. Then he drew up.

Henry was still laughing helplessly. “I’m—sorry!” she gasped.

“Mm. –Hell and damnation,” muttered Mr Tarlington, looking at his reins and at the feisty team poled up. “Uh—oh, well.” Transferring the reins to his whip hand, he put the other arm firmly round Henry’s shoulders. This produced no visible reaction.

“Will you—” He broke off. “For God’s sake STOP LAUGHING!” he shouted.

“I’m—trying—to!” gasped Henry helplessly.

“For God’s SAKE! Henry!” shouted the driven Mr Tarlington. “I’m trying to ask you to MARRY me!”

“I—know!” gasped Henry helplessly.

“WILL YOU?” he shouted.

“I’ll have to: your buh-butler expects— Ow!” wailed Henry, collapsing in further paroxysms.

Mr Tarlington released his beloved’s shoulders and passed that hand over his face. “God,” he muttered.

After quite some time Henry managed to gulp and say: “I’m so sorry.”

“That’s quite all right,” he said heavily. “At least you were spared damned Tomkins drinking our health in Papa’s brandy.”

“Help, did he?”

“Mm. –He’s gone to fetch Wilf. Uh—forgot I’d arranged to meet up with him,” explained Mr Tarlington sheepishly.

“Oh, good, so he’s coming down to the Place?”

“Yes; he should be in nice time to congratulate us,” he said pointedly.

“I’m awfully sorry,” said Henry in a small voice.

Aden went rather white. “Sorry for what?”

“Laughing,” replied Henry glumly. “I thought that that stupid foreign trip and all that nonsense might have cured me. Um—I mean, turned me into a real lady.”

Aden’s mouth twitched. “And it didn’t?”

“No,” said Henrietta glumly.

His shoulders shook. “That’s good.”

“Is it?” she said numbly.

Mr Tarlington looked down at her, and smiled. “Yes. I don’t want to marry a lady, I want to marry Henry Parker, one-time wearer of boy’s breeches, ex-sophisticated foreign traveller, and failed real lady. You look damned ridiculous in that fur of Mamma’s, by the by.”

“I know. Your mamma’s maid chose it. Well, the housekeeper—I was going to say helped. Aided and abetted her.”

“Mm.” Aden put his hand under her chin.

“Your mother’s maid did this ladylike bow.”

“I don’t wish to know. I love you. Do you love me?”

Henry blushed. “I know I didn’t at first: I thought you were old and... I was stupid. Well, I never thought of myself as the sort of person that could fall in love, you see. But I’ve always liked you,” she said earnestly.

“Is—is this a ‘no’?” said Aden in a voice that shook, in spite of himself.

“No!” cried Henry in amaze. “I mean, of course it isn’t! I mean, it’s a ‘yes’!”

Mr Tarlington gave up trying to make his beloved say she loved him in so many words, and kissed her very thoroughly.

Henry smiled, and sighed, and blushed, and smiled again.

“If that compares ill—or even well, come to think of it—with any of those foreign kisses you received on your Continental tour, I don’t wish to hear it!”

“You’re jealous,” discovered Miss Parker slowly.

“You’re damned right I’m jealous! I’ve waited—” Aden broke off, biting his lip. “I swore I wouldn’t mention that. It wasn’t your fault that you were too damned young when we met.”

“Um—no,” said Henry, looking at him nervously. He was staring straight ahead, scowling. She put her hand timidly on his.

“Bringing this cursed curricle was a damned mistake,” admitted Aden shakily. “I can’t kiss you properly. Never mind: come here.”

He put one arm round her and kissed her again. This time Henry sighed deeply and put her head on his shoulder, considerably crushing the smart bonnet and ladylike bow.

“I have a sinking feeling that our mothers are planning a monster of a wedding for July: after Alfreda’s baby, you see. Can you bear it?” he murmured.

“Mm. Do we have to talk about it just now?” said Henry in a dreamy voice.

“No, by God, we don’t!” replied Mr Tarlington with feeling.

“Well?” said Mrs Fairbrother, quite some weeks later, to her visitor in Oxford, with a twinkle in her eye. “Dare I ask, what made you decide in favour of matrimony in the end, Pansy?”

Pansy laughed a little. “I think you must know that although I could advance many reasons, some of them almost rational-seeming and logical, some representing an entirely proper sentiment, and even some which indicate a developing womanly sensibility on the part of the subject, I cannot explain it, Mrs Fairbrother! Except to say, I suppose I—I gave in to the fact that I love him, after all.”

The former Miss Blake nodded and smiled. “That is all one can truly say, in the end!”

Mrs Parker, of course, had known it all, all along, and did not fail to tell all her acquaintance so. Fortunately most of them were as pleased as she over the engagements of her daughter and niece. and kindly did not correct her.

Mr Rowbotham, rather more surprisingly, also claimed to have known it all along. At the least, Aden’s and Henry’s.

“Said so all along,” he remarked smugly to a pleasant conclave of gentlemen which had convened at Chipping Abbas, possibly in order to help its master get it into order for his July wedding.

“To whom, Wilf?” replied Aden sweetly.

“Everyone!” said the elegant one huffily. “Said so to you, Noël, did I not?”

“Did you?” replied Sir Noël Amory blankly.

“Yes! Um—think so. Might have been Harley Quayle-Sturt.”

“What precisely was it, that you said?” asked Theo Parker with a twinkle in his eye.

“Eh? Aden and the little Dark Star, of course!” replied Mr Rowbotham huffily. “Your sister! Um—ain’t she? –Yes,” he answered himself.

“Never let it be said a Rowbotham cannot hold its brandy-—though it can’t,” explained Mr Tarlington smoothly.

Regrettably, the proper Mr Parker at this collapsed in splutters. So did Mr Ludo Parker.

“We shall agree that you said it all along, Wilf,” said Sir Noël kindly, “though I seem to remember a point at which you said Aden’s ma clearly intended the Golden Star’s fortune for him.”

“I never! Not sayin’ that some fellows might not have done so—well, wasn’t they takin’ bets on it at White’s at one stage? But I have always said—and so I will always maintain,” he said, pointing an awful finger at him, “that it were Aden and the little Dark Star all along.”

Sir Noël was just beginning peaceably: “Very well, then, Wilf,” when the elegant one amended with a frown: “That is, if she were the one whose breeches he dusted that time. Uh—were she?”

“That silence you hear, Parker,” explained Mr Tarlington kindly to his almost-brother-in-law, “is the company bein’ bereft of speech. Don’t ask me for the details: I don’t feel strong enough to explain ’em.”

Smiling very much, Theo replied: “Well, I think I have a fairly good idea of them, Aden. But I do so agree: if he’s forgotten them, let us not recall them to his mind!”

“I’m just saying!” said Mr Rowbotham loudly and crossly. “Remember it perfectly well! Remember it as if it were yesterday! You was there,” he said to Ludo, “pointing a damned gun at our heads.”

“No! It wasn’t me, it was Egg!”

“Don’t bother, lad, he will not remember a word in the morning,” explained Sir Noël kindly.

Loftily ignoring this, Mr Rowbotham continued: “And uh—yes, I have it: dashed Vyv Gratton-Gordon, riding a great brute of a—”

“It was Rupert, y’fool,” sighed Mr Tarlington.

“That’s what I’m saying! Riding a dashed raw-boned brute of a thing. Remember it as if it were yesterday: parcel of damned lads choused ten guineas out of me over a dashed grey fightin’ cock,” he said, eyeing Ludo frostily.

“Ignore it,” advised Sir Noël, as Ludo’s cheeks reddened.

“That grey,” said Mr Rowbotham with great dignity to his oldest friends, ‘“was squeezed. And so I shall always maintain.”

“And?” drawled Sir Noël.

“Eh? Well, nothing: whole point. Squeezed.”

“Shut it, Wilf,” said Noël heavily, “and for God’s sake let’s drink a toast to the happy couple! Come on, fill your glasses! To Aden and—”

“Aden and the Golden Star,” agreed Mr Rowbotham blearily, smiling. “No, dammit, that’s wrong. Your one, then, Noël! Little boating gal!

“That’ll do, I think,” decided Mr Tarlington as Sir Noël’s jaw dropped. “OY! Wilf! Bed!”

“We’ll take him,” said Theo hurriedly, getting up. “Come on, Ludo.” The Parker brothers grasped Mr Rowbotham’s arms strongly.

“Didn’t mean Lady W.,” he explained as they headed for the door.

“Shut it, Wilf,” sighed Mr Tarlington.

“Pretty little lass: forget her name.”

“She’s marrying Lavery!” snapped Mr Tarlington, nearing the end of his tether. “And shut it!”

“That’s what I’m saying: good luck to her,” he said blearily as they bore him from the room. “Would never have—hic!—done for Noël. –No dresh shenshe,” they heard him explaining to the Parkers as the door mercifully closed behind him.

Aden cleared his throat.

“He’s right, you know: no dress sense at all,” said Sir Noël calmly. He raised his glass. “To you and Henrietta, Aden.”

“At last!” replied Aden, grinning. “Thanks, Noël.”

… “But the extraordinary thing is,” explained Mrs Parker brightly to a smiling but plainly bewildered Lady Georgina Claveringham, as the multicoloured myriads of guests at the brilliant Tarlington-Parker July wedding chattered and cackled like so many noisy bright parrots, “that without the Ogilvie connection, none of it would ever have happened!”

“She has it all wrong!” hissed the very new Mrs Tarlington in her husband’s ear with an agonized expression.

“Mm, well, she certainly has several glasses of champagne inside her!” admitted Aden. He looked slowly round the gay throng: his shrewd grey eyes twinkled. Little Lady Lavery and her sister-in-law Mrs Winnafree, the one adorable in pink silk, the other exquisitely dainty in palest blue silk, both hanging on their very recent husbands’ arms, were in a happy little group with Fliss and Rupert, and Mr and Mrs Colonel Amory; just nearby, Lady Sarah Quayle-Sturt and Lady Jane Carey, with their husbands, were smiling and chatting with Dr and Mrs Fairbrother, Mr Theo Parker and, quite coincidentally, Jane’s and Sarah’s sister May.

“But I would not say, for all that, she has it positively wrong!” he concluded with a laugh.

Which completes

THE OGILVIE CONNECTION

But we will learn how Sir Noël Amory meets his match in

No comments:

Post a Comment